Making Infused Herbal Vinegars: Your Complete Beginner’s Guide

Vinegars extract minerals/vitamins that oil/alcohol can’t, create mineral-rich tonics (especially nettles), preserve fresh herbs, dual use (culinary + medicinal). DIY $3-5 vs. commercial $15-25.

What This Guide Will Teach You

Vinegar has been used in herbal medicine for thousands of years—from ancient Roman oxymels to traditional fire cider preparations. When you infuse herbs in vinegar, you’re creating a unique type of extract that excels at pulling minerals from plants, preserving herbs indefinitely, and supporting digestive health.

This guide will teach you how to make mineral-rich tonics, digestive bitters, and flavorful culinary vinegars that bridge food and medicine. You’ll learn why vinegar works so differently from other solvents, which herbs are perfectly suited to vinegar extraction, and how to avoid the common mistakes that can ruin a batch. By the end, you’ll be confidently making vinegar infusions that support bone health, digestion, and overall vitality.

What Exactly Is an Infused Vinegar?

An infused vinegar is simply herbs steeped in vinegar (usually apple cider vinegar) for 2-4 weeks, allowing the acetic acid to extract and preserve medicinal compounds—particularly minerals that other solvents can’t effectively pull from plant material.

Unlike water-based teas that extract some minerals, or alcohol tinctures that extract resins and alkaloids, vinegar has a unique superpower: it converts insoluble mineral salts bound in plant cell walls into highly bioavailable, soluble acetate salts that your body can easily absorb.

Why This Matters

Your body needs minerals—calcium for bones, magnesium for muscles and nerves, iron for blood, potassium for heart function, silica for connective tissue. While you can get minerals from food, certain herbs are mineral powerhouses. But here’s the challenge: those minerals are often locked into tough plant structures.

Vinegar’s acidity acts like a chemical key, unlocking these minerals and making them available. When you drink a tablespoon of nettle vinegar in water, you’re getting bioavailable calcium, magnesium, iron, and other minerals in a form your digestive system can readily use.

Plus, vinegar itself has therapeutic properties—it may support healthy blood sugar regulation, improve mineral absorption in the gut, and stimulate digestive secretions.

The Science Behind How Vinegar Extraction Works

Understanding the chemistry helps you make better vinegars.

Vinegar Composition

Acetic acid: 5-7% in typical vinegar (store-bought or homemade) Water: 93-95% Minor components: Trace minerals, organic acids, phenolic compounds (in apple cider vinegar)

This combination creates a unique extraction medium that’s both acidic (pH 2-3) and aqueous (water-based).

Mineral Extraction: The Magic of Acetate Salt Formation

This is vinegar’s true superpower.

The problem: Minerals in plants are typically bound as carbonates, oxides, or phosphates—compounds that are poorly soluble in water and not readily absorbed by the digestive system.

The solution: Acetic acid reacts with these insoluble mineral compounds to form soluble acetate salts.

Chemical example (calcium extraction):

CaCO₃ (insoluble calcium carbonate in plant) + 2 CH₃COOH (acetic acid) → Ca(CH₃COO)₂ (soluble calcium acetate) + H₂O + CO₂

The calcium acetate dissolves in the vinegar and becomes highly bioavailable when you consume it.

This same process works for:

Magnesium: Mg(CH₃COO)₂ (magnesium acetate)

Iron: Fe(CH₃COO)₂ (iron(II) acetate)

Potassium: CH₃COOK (potassium acetate)

Calcium: Ca(CH₃COO)₂ (calcium acetate)

Why this matters: Studies suggest that acetate forms of minerals may be absorbed as well or better than other forms. The acidic environment also supports absorption by preparing minerals for uptake in the small intestine.

What Else Vinegar Extracts

Beyond minerals, vinegar’s dual nature (acidic + aqueous) extracts:

Some alkaloids (as acetate salts): Many alkaloids are weakly basic. Acetic acid converts them to soluble salts, improving extraction.

Polyphenols and flavonoids: The water component extracts these antioxidant compounds.

Some volatile oils: Though less effectively than alcohol or oil, vinegar does capture some aromatic compounds.

Bitter principles: Compounds that stimulate digestion extract well.

Preservation Mechanism

Vinegar’s low pH (2-3) creates an environment where virtually no microorganisms can survive:

- Bacteria: Need pH > 4.5 to grow

- Molds: Need pH > 3.5

- Yeasts: Need pH > 3.0

This means properly made vinegar infusions last for years without refrigeration—the acidity itself is the preservative.

The “Mother” in Raw Apple Cider Vinegar:

If you’ve seen cloudy strands floating in raw apple cider vinegar, that’s the “mother”—a biofilm of acetic acid bacteria (primarily Acetobacter species) and cellulose.

What it does:

- Indicates an unpasteurised, living product

- Contains beneficial bacteria that may support gut health

- Provides trace enzymes

Do you need it?: Not essential for herbal extraction (the acetic acid does the work), but many herbalists prefer raw vinegar with the mother for its potential additional benefits.

When to Use Infused Vinegar (And When Not To)

Perfect For:

Mineral-rich herbs: Nettle, oatstraw, horsetail, red clover, dandelion leaf. Vinegar is THE method for maximum mineral extraction and bioavailability.

Bone health support: The extracted calcium and magnesium support skeletal health. Traditional tonics for osteoporosis prevention often use vinegar-extracted herbs.

Digestive support: Vinegar stimulates stomach acid production and digestive enzyme secretion. Taking herb-infused vinegar before meals (diluted in water) supports digestion.

Bitter herbs: Dandelion root, burdock root, gentian, orange peel. The bitterness combined with vinegar’s acidity creates powerful digestive tonics.

Culinary applications: Herb vinegars make delicious salad dressings, marinades, and cooking ingredients—food as medicine.

Immune support formulas: Traditional “fire cider” preparations combine pungent, antimicrobial herbs with vinegar for cold/flu season.

Not Ideal For:

People with active ulcers or severe acid reflux: The acidity may aggravate these conditions (though paradoxically, small amounts of vinegar sometimes help mild reflux by improving stomach acid adequacy).

Highly resinous herbs: While vinegar extracts some compounds, alcohol is superior for resins, waxes, and very lipophilic compounds.

Alkaloid-rich herbs requiring neutral/basic pH: Some compounds degrade in acid (though this is relatively rare).

People who dislike vinegar taste: While dilutable, vinegar infusions retain their characteristic tanginess.

Your First Infused Vinegar: The Basic Method

Let’s walk through making your first batch.

What You Need

Ingredients:

- Dried or fresh herbs of your choice

- Raw apple cider vinegar with the mother (preferred) or other vinegar

- Optional: honey for oxymel preparation

Equipment:

- Glass jar with plastic lid or wax paper/parchment under metal

lid (vinegar corrodes metal) - Cheesecloth or fine strainer

- Dark glass bottles for storage

- Labels

Why plastic lid matters: Acetic acid reacts with metal, causing corrosion, rust, and metallic contamination of your vinegar. Always use plastic lids, or place wax paper/parchment paper between jar and metal lid as a barrier.

The Step-by-Step Process

Step 1: Choose and prepare your herbs

For your first vinegar, good beginner choices:

Nettle (mineral-rich, mild flavour)

Rosemary (culinary, aromatic)

Thyme (antimicrobial, pleasant)

Garlic (immune support, distinctive)

Dried herbs work well. Fresh herbs are also excellent for vinegar (unlike oils where fresh herbs pose botulism risk)—the acidic environment prevents dangerous bacterial growth.

Chop or crush herbs to increase surface area for extraction.

Why fresh herbs are safe in vinegar: The pH of 2-3 is inhospitable to Clostridium botulinum (botulism bacteria) and virtually all pathogens. This is why vinegar is a traditional food preservative.

Step 2: Fill jar 1/2 to 2/3 full with herbs

Place herbs in your jar. For dried herbs, fill about 1/2 full. For fresh herbs, you can fill 2/3 full (they’ll compact as vinegar extracts moisture).

Why this ratio: Sufficient herbs for good extraction without overcrowding, allowing vinegar to circulate and fully contact all plant material.

Step 3: Cover completely with vinegar

Pour vinegar over herbs, ensuring they’re completely submerged with at least 2-3cm vinegar above the top herbs.

Stir or poke with a chopstick to release air bubbles.

Why complete coverage matters: Any herbs exposed to air can develop mold (though less likely than with other menstruums due to vinegar’s antimicrobial properties).

Step 4: Seal with plastic lid

Put plastic lid on tightly, or place wax paper/parchment between jar and metal lid, then screw lid on.

Label with:

- Herb(s) used

- Vinegar type

- Date started

Step 5: Store in cool, dark place

Place jar in cupboard away from heat and light. Room temperature is fine—no special conditions needed.

Why dark and cool: Some compounds (like chlorophyll) degrade with light exposure. Cool, stable temperature prevents evaporation and maintains quality.

Step 6: Shake daily

Once daily, shake the jar well. This:

- Redistributes herbs

- Moves fresh vinegar into contact with herbs

- Speeds extraction

- Prevents settling

Step 7: Infuse for 2-4 weeks

Minimum: 2 weeks for decent extraction Standard: 4 weeks for optimal extraction Extended: 6-8 weeks won’t hurt and may increase potency further

The longer you infuse, the more complete the extraction.

Step 8: Strain thoroughly

After infusion period, strain through fine-mesh strainer or several layers of cheesecloth.

Press or squeeze the herbs to extract all vinegar—they absorb significant liquid.

Compost spent herbs.

Step 9: Bottle and store

Pour strained vinegar into clean glass bottles (dark glass preferred).

Label clearly with:

- Herb(s)

- Date strained

- Dilution instructions (e.g., “1 tablespoon in glass of water”)

Step 10: Store and use

Store in cool, dark location. Properly made vinegar infusions last 1-2+ years.

How to use:

Mineral tonic: 1-2 tablespoons in glass of water daily

Digestive bitter: 1 teaspoon in water before meals

Culinary: Use in salad dressings, marinades, cooking

Oxymel (vinegar + honey): Mix equal parts infused vinegar and honey, take by teaspoon

Your First Project: Nettle Mineral Tonic

Let’s make something with real therapeutic value.

Nettle Vinegar for Bone and Blood Health

Why nettle?

Nettle (Urtica dioica) is one of the most mineral-dense herbs available:

Calcium: 300-400 mg per 100g dried leaf

Magnesium: 70-100 mg per 100g

Iron: 4-6 mg per 100g

Silica: Significant amounts (supports connective tissue)

Potassium: 600-700 mg per 100g

Vitamin K: Important for bone health

Traditional use: Anemia, osteoporosis prevention, arthritis, hair and nail health, allergies.

What you need:

- 50-75g dried nettle leaves (fills pint jar about 1/2 full)

- 400-500ml raw apple cider vinegar with mother

- Pint (500ml) jar with plastic lid

- Strainer and cheesecloth

How to make it:

Fill pint jar 1/2 full with dried nettle leaves

Cover completely with apple cider vinegar plus 3cm extra

Poke with chopstick to release air bubbles

Seal with plastic lid, label with date

Store in cupboard for 4 weeks

Shake daily

Strain well, pressing herbs to extract all vinegar

Bottle in clean jar, label

How to use it:

Daily tonic: 1-2 tablespoons in glass of water (250ml), sipped

Timing: Morning for energy, or divided through day

Long-term use: Minerals build gradually—use daily for 3-6 months to notice effects

Taste: Slightly salty-mineral flavour, quite pleasant when diluted

Cost breakdown (NZ):

Dried nettle: $10-18/50g

Apple cider vinegar: $6-10/500ml

Jar: Reuse or $2-5

Total: $18-35 for 400-450ml finished tonic

This provides approximately 25-30 servings (1-tablespoon doses). Compare to commercial mineral supplements at $20-40/month, and you’re getting superior, whole-herb nutrition for less cost.

Where to Source Your Materials in New Zealand

Vinegar

Apple cider vinegar:

- $6-12/500ml)

- Health food stores: Various organic brands ($8-15/500ml)

- Look for “with the mother” and “raw” on label

Other vinegars:

- White wine vinegar: Lighter flavour for delicate herbs

- Red wine vinegar: Richer flavour for culinary uses

- Rice vinegar: Mild, slightly sweet

- Avoid distilled white vinegar for medicinal use (harsh, no mother)

Dried Herbs

Same sources as other preparations:

- Bin Inn (good bulk selection, reasonable prices)

- Health food stores

- Online herbal suppliers

- Grow and dry your own

Prices: $8-20 per 50g for most dried herbs.

Fresh Herbs

From your garden: Ideal—harvest at peak freshness Farmers’ markets: Seasonal availability Supermarkets: Common culinary herbs year-round

Fresh vs. dried for vinegar: Both work excellently. Fresh herbs create more aromatic, vibrant vinegars. Dried herbs are more concentrated in minerals.

Supplies

Jars: Reuse pickle or pasta sauce jars. Check lids are plastic or plan to use wax paper barrier.

Plastic lids: Kitchen supply stores, online packaging suppliers (\$2-5 per lid depending on size).

Specific Herbs That Excel in Vinegar Infusions

For Mineral Support

Nettle (Urtica dioica): Already covered above. The gold standard mineral herb.

Oatstraw (Avena sativa): Green oat stems and leaves harvested before grain matures. Rich in:

- Silica (supports hair, skin, nails, connective tissue)

- Calcium and magnesium (bone health)

- B-vitamins

Traditional use: Nervous system support, bone health, skin health. Gentle, nourishing.

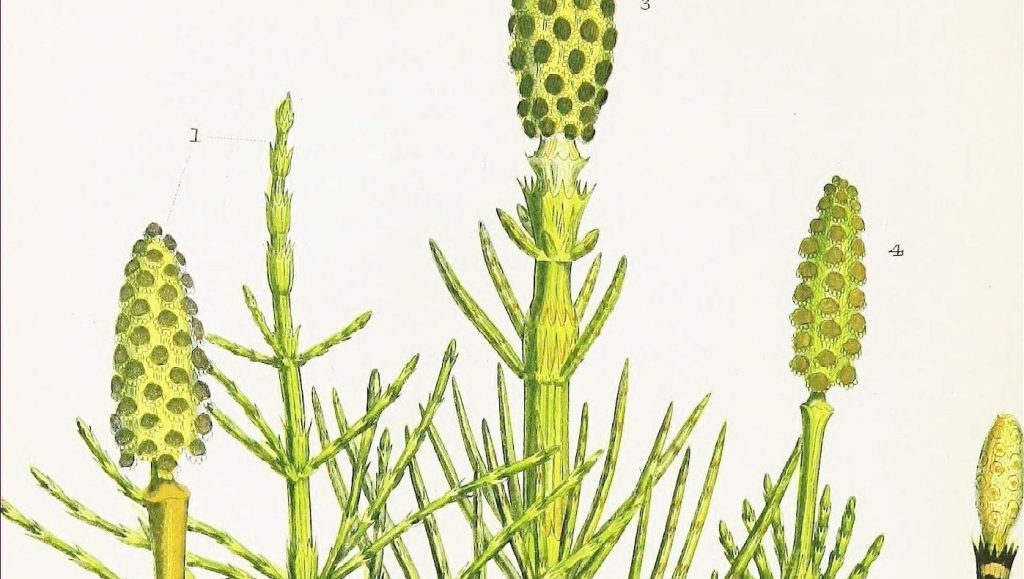

Horsetail (Equisetum arvense): Exceptionally high in silica (up to 35% of plant weight). Also contains:

- Calcium, magnesium, potassium

- Flavonoids

Traditional use: Connective tissue support, hair/nail/skin health, bladder health.

Safety note: Use in moderate amounts—very high in silica. Not for long-term daily use in large amounts. Avoid if kidney disease present.

Red clover (Trifolium pratense): Mineral-rich blossoms containing:

- Calcium, magnesium

- Isoflavones (phytoestrogenic compounds)

Traditional use: Menopause support, bone health, skin health.

For Digestive Support

Dandelion root (Taraxacum officinale): Bitter root that stimulates digestion. Contains:

- Potassium (explains diuretic effect)

- Inulin (prebiotic fibre)

- Bitter principles

Vinegar extracts: Minerals and bitter compounds.

Use: 1 teaspoon in water before meals to stimulate digestive secretions.

Burdock root (Arctium lappa): Earthy, slightly sweet root. Contains:

- Minerals (iron, potassium, magnesium)

- Inulin (prebiotic)

- Polyacetylenes (antimicrobial)

Traditional use: Digestive support, blood purification, skin health.

Orange peel: Dried citrus peel. Contains:

- Bitter principles

- Essential oils (limonene)

- Flavonoids

Use in digestive bitters—bitter orange peel stimulates digestion while adding pleasant flavour.

For Immune Support: Fire Cider

Fire cider is a traditional immune-stimulating preparation using pungent, antimicrobial herbs in vinegar:

Traditional ingredients:

- Horseradish root (antimicrobial, stimulating)

- Garlic (antimicrobial, immune-boosting)

- Onion (antimicrobial, mineral-rich)

- Ginger (anti-inflammatory, warming)

- Turmeric (anti-inflammatory)

- Chili peppers (circulatory stimulant)

- Lemon (vitamin C, flavour)

Method: Chop all ingredients, pack in jar, cover with vinegar, infuse 4-6 weeks. Strain, add honey to taste. Take 1-2 tablespoons daily during cold season or at first sign of illness.

Effect: Stimulates circulation, supports immune function, provides antimicrobial compounds.

For Culinary Use

Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis): Aromatic herb. Creates delicious vinegar for:

- Salad dressings

- Roasted vegetables

- Marinades

Thyme (Thymus vulgaris): Similar to rosemary—aromatic, antimicrobial, culin culinary.

Garlic (Allium sativum): Fresh cloves create pungent, flavorful vinegar. Antimicrobial, cardiovascular support.

Basil, oregano, tarragon: All create wonderful culinary vinegars.

Advanced Technique: Oxymels

Oxymels are ancient preparations combining vinegar and honey.

Method:

Make standard herbal vinegar

After straining, combine equal parts infused vinegar and raw honey

Shake vigorously until honey dissolves (warming gently helps)

Bottle and label

Why:

- Makes vinegar more palatable

- Combines honey’s therapeutic properties with vinegar and herbs

- Traditional for respiratory support (honey soothes, vinegar provides

antimicrobial and expectorant action)

Use: Take by spoonful straight or diluted in warm water.

Traditional formula: Elderberry-thyme oxymel for coughs and sore throats.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Cloudiness in finished vinegar

Cause: Normal with raw vinegar—indicates active cultures (mother). Also occurs when vinegar extracts plant compounds.

Solution: Not a problem unless accompanied by foul odor. If smell is bad, discard. Otherwise, cloudiness is normal and acceptable.

Problem: Mold on surface

Cause: Herbs not fully submerged, or jar opened frequently allowing air exposure.

Solution: Discard entire batch (mold can produce toxins). Prevention: Keep herbs submerged, don’t open jar during infusion.

Problem: Weak extraction, little flavour/colour

Cause: Not enough herbs, insufficient time, or old/low-quality herbs.

Solution: Use more herbs (fill jar 1/2 to 2/3 full), infuse longer (try 6-8 weeks), use fresh, aromatic herbs.

Problem: Vinegar tastes too strong

Cause: That’s vinegar! It’s meant to be diluted.

Solution: Always dilute 1:8 to 1:15 in water (1 tablespoon in 120-250ml water). Or make into oxymel with honey. Or use in salad dressings where acidity is desirable.

Problem: Metal lid corroded

Cause: Acetic acid reacting with metal.

Solution: Discard if significant rust contamination. Next time use plastic lid or wax paper barrier. Strain vinegar through coffee filter if concerned about metal particles.

Safety Considerations

Acid-related concerns:

Tooth enamel: Always dilute vinegar in water, never take straight. Rinse mouth after consuming.

Digestive sensitivity: Some people experience heartburn or upset stomach. Start with small doses (1 teaspoon) and increase gradually.

Active ulcers or severe GERD: Consult healthcare provider before use.

Medication interactions:

Diabetes medications: Vinegar may lower blood sugar. Monitor levels carefully.

Diuretics: Nettle and other herbs plus vinegar may increase potassium—discuss with doctor if on potassium-sparing diuretics.

Herb-specific cautions:

Horsetail: Not for long-term high-dose use, avoid with kidney disease

Nettle: Generally very safe, rare mild digestive upset

Dandelion: Check for allergies (Asteraceae family)

Budget-Friendly Infused Vinegars

Ultra-low-cost nettle mineral tonic ($2-3 per batch):

- Foraged nettles: FREE (abundant NZ weed)

- Apple cider vinegar: $4-6/L = $2-3 per 500ml batch

- Recycled jar: FREE

Total: $2-3 (makes 500ml mineral-rich tonic)

Free herb options: Nettles, dandelion, plantain, cleavers, rosemary, thyme (from garden), elderflower (seasonal).

This makes mineral supplementation accessible regardless of budget.

Storage and shelf life:

- Properly made vinegar infusions last 1-2+ years

- Store cool, dark, tightly sealed

- Discard if mold develops or smell becomes foul

Building Your Vinegar Practice

Start simple. Make one mineral-rich vinegar using nettle or oatstraw. Use it daily, diluted in water. Notice how you feel over weeks and months.

Then expand. Try digestive bitters before meals. Create culinary vinegars for cooking. Make fire cider for immune season.

As you gain experience, you’ll develop favorites. You’ll learn which herbs work best for your needs, which combinations you enjoy, how diluted you prefer your doses.

Vinegar infusions are wonderfully forgiving. They last forever, they’re safe to experiment with (within herb safety guidelines), and they bridge food and medicine beautifully. A bottle of herb vinegar in your cupboard is ready whenever you need minerals, digestive support, or a flavour boost to your cooking.

This is practical herbalism at its finest: simple preparation, profound benefits, ancient wisdom validated by modern understanding.

Sources & Further Reading

Books:

- Katz, S. E. (2012). The Art of Fermentation. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- McBride, K. (2019). The Herbal Kitchen. Conari Press.

- Gladstar, R. (2012). Rosemary Gladstar’s Medicinal Herbs: A Beginner’s Guide. Storey Publishing.

Scientific Literature:

- Johnston, C. S., & Gaas, C. A. (2006). Vinegar: medicinal uses and

antiglycemic effect. Medscape General Medicine, 8(2), 61. - Samad, A., Azlan, A., & Ismail, A. (2016). Therapeutic effects of

vinegar: a review. Current Opinion in Food Science, 8, 56-61.

New Zealand Resources:

- Local herb suppliers and nurseries

- Bin Inn bulk stores

- Community gardens for growing herbs

Disclaimer: Does not represent rongoā Māori methods. For rongoā knowledge, consult Te Paepae Motuhake.

Medical: This guide is for educational purposes only and is not medical advice. Herbal vinegar infusions are appropriate for supporting general health and minor conditions. If you are pregnant, nursing, taking medications (especially diabetes medications or diuretics), or have digestive conditions like active ulcers, seek guidance from a qualified health practitioner before using. Properly identify all herbs. The information about plant constituents and traditional uses is educational in nature.

Note on Pricing: All prices mentioned in this guide are approximate and based on New Zealand suppliers as of December 2025. Prices vary by supplier, season, and market conditions. We recommend checking current prices with your local suppliers.