Understanding Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Mechanisms

This comprehensive guide explores the molecular mechanisms underlying herb-drug interactions, providing evidence-based information for informed decision-making in clinical and personal contexts.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Complexity of Herb-Drug Interactions

- Pharmacokinetic Interactions: ADME Processes

- Pharmacodynamic Interactions: Target-Level Effects

- Critical High-Risk Herbs

- Medication-Specific Interaction Profiles

- Clinical Assessment and Risk Prediction

- New Zealand-Specific Considerations

- Evidence Levels and Research Limitations

Introduction: The Complexity of Herb-Drug Interaction

The Fundamental Challenge

Unlike pharmaceutical drugs (single purified compounds), herbal medicines contain hundreds to thousands of bioactive constituents. Each constituent may interact with the body differently, creating complex multi-target, multi-pathway effects. This pharmaceutical versus herbal comparison:

Pharmaceutical Drug:

- Single chemical entity

- Predictable pharmacokinetics

- Well-defined mechanism of action

- Standardised potency

- Extensive safety data

Herbal Medicine:

- 200-1000+ compounds per plant

- Variable pharmacokinetics (synergistic effects)

- Multiple mechanisms simultaneously

- Natural variation in potency

- Limited clinical interaction studies

Result: Herb-drug interaction potential is theoretically higher than drug-drug interactions, yet clinical data is far more limited.

Prevalence and Clinical Significance

Usage statistics:

- Approximately 40-50% of New Zealand adults use complementary medicines

- 70-80% of cancer patients use complementary therapies

- 60-70% don’t inform their doctors about herb use

Clinical consequences:

- Most interactions are pharmacokinetic (affecting drug levels 20-90%)

- Serious interactions documented: transplant rejection, treatment failure, toxicity, bleeding, arrhythmias

- Mechanisms range from minor (timing-dependent absorption) to major (enzyme induction changing systemic metabolism)

Pharmacokinetic Interactions: ADME Processes

Pharmacokinetics describes what the body does to a drug: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion.

Absorption-Level Interactions

Mechanism 1: Efflux Transporter Modulation (P-glycoprotein)

P-glycoprotein (P-gp, MDR1, ABCB1) is an ATP-dependent efflux pump in intestinal epithelium that pumps drugs back into the gut lumen, limiting absorption.

Key herbs affecting P-gp:

- St John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): Hyperforin induces P-gp expression via pregnane X receptor (PXR) activation → increased efflux → reduced drug bioavailability

- Grapefruit juice: Paradoxically inhibits intestinal P-gp (but also inhibits CYP3A4) → complex effects

- Piperine (Black pepper): Inhibits P-gp → increased drug absorption

Clinical example: St John’s Wort reduces digoxin bioavailability by 25% through P-gp induction. Digoxin is a P-gp substrate with narrow therapeutic index (0.5-2.0 ng/mL therapeutic, >2.5 ng/mL toxic).

Mechanism 2: Uptake Transporter Modulation (OATPs)

Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptides (OATPs) facilitate drug absorption. Herbs containing polyphenols can inhibit OATPs.

Example: Grapefruit juice inhibits OATP1A2, reducing absorption of fexofenadine (antihistamine), atenolol (beta-blocker), and some statins.

Mechanism 3: Chelation and Complex Formation

Metal-containing herbs can chelate drugs, preventing absorption.

Examples:

- Iron, calcium, magnesium: Bind tetracycline antibiotics, forming insoluble complexes

- Tannin-rich herbs (green tea high doses, witch hazel): Precipitate proteins and alkaloids

Clinical significance: Separate doses by 2-4 hours.

Mechanism 4: pH-Dependent Absorption Changes

Gastric pH affects drug ionisation and solubility.

Example: Antacids containing calcium/magnesium elevate gastric pH, reducing absorption of pH-dependent drugs (ketoconazole, atazanavir).

Metabolism-Level Interactions: Cytochrome P450 System

The Critical System: Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes metabolise 70-80% of all drugs. Major isoforms:

- CYP3A4/5: ~50% of all drug metabolism (statins, calcium channel blockers, immunosuppressants, benzodiazepines, many others)

- CYP2D6: ~25% (many antidepressants, beta-blockers, opioids)

- CYP2C9: ~15% (warfarin, NSAIDs, sulfonylureas)

- CYP2C19: ~10% (proton pump inhibitors, some antidepressants)

- CYP1A2: Caffeine, theophylline, some antipsychotics

Enzyme Induction: The St John’s Wort Example

Hyperforin (primary constituent in Hypericum perforatum) is a potent ligand for the pregnane X receptor (PXR). PXR activation:

- PXR (nuclear receptor) binds hyperforin

- PXR translocates to nucleus

- PXR binds DNA response elements

- Upregulates transcription of CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, P-gp

- Increased enzyme protein synthesis

- Enhanced drug metabolism → reduced drug levels

Timeline:

- Initiation: 3-7 days (time for enzyme synthesis)

- Maximum effect: 10-14 days

- De-induction after stopping: 1-2 weeks (enzyme protein half-life)

Clinical magnitude: CYP3A4 induction up to 3-5 fold → drug levels reduced 40-90%

Documented interactions:

- Cyclosporine: AUC reduced 46-62% (transplant rejection risk)

- Oral contraceptives: Ethinyl estradiol AUC reduced 13-15%, breakthrough bleeding, pregnancies documented

- Warfarin: INR decreased, thrombosis risk

- Protease inhibitors (indinavir): AUC reduced 57-81% (HIV treatment failure)

Critical point: Daily hyperforin dose >1mg produces clinically significant induction. Standard St John’s Wort extracts contain 3-6mg hyperforin per daily dose.

Enzyme Inhibition: The Grapefruit Juice Example

Furanocoumarins (bergamottin, 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin) in grapefruit irreversibly inhibit intestinal CYP3A4:

- Furanocoumarin binds CYP3A4 active site

- Forms covalent adduct (mechanism-based inhibition)

- Enzyme permanently inactivated

- New enzyme synthesis required (24-72 hours)

- Reduced first-pass metabolism → increased drug bioavailability

Clinical magnitude: Single 200mL glass can inhibit intestinal CYP3A4 >50% for 24-72 hours.

Affected drugs:

- Simvastatin: AUC increased 16-fold → rhabdomyolysis risk

- Felodipine: AUC increased 2-3 fold → hypotension

- Buspirone: AUC increased 9-fold → excessive sedation

Why grapefruit affects some statins but not others:

- Highly affected: Simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin (high first-pass metabolism)

- Minimally affected: Rosuvastatin, pravastatin, fluvastatin (low first-pass metabolism or different metabolic pathway)

Other CYP Inhibiting Herbs:

- Goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis): Berberine inhibits CYP3A4, CYP2D6 (competitive inhibition)

- Kava (Piper methysticum): Kavalactones inhibit CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP1A2

- Milk thistle (Silybum marianum): Silymarin inhibits CYP3A4, CYP2C9 (in vitro; clinical significance unclear)

Important consideration: In vitro inhibition doesn’t always translate to clinical significance. Achieving sufficient systemic concentrations is required.

Phase II Metabolism: Conjugation Reactions

Phase II enzymes (UGTs, SULTs, GSTs) add polar groups (glucuronide, sulfate, glutathione) to make drugs more water-soluble for excretion.

Herb effects on Phase II:

- St John’s Wort: Induces UGT1A1 (metabolizes irinotecan, bilirubin)

- Green tea (high doses): Catechins inhibit COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase), affecting methyldopa and L-dopa metabolism

Excretion-Level Interactions

Renal Excretion:

Some herbs affect renal drug transporters (OAT1, OAT3, OCT2) or alter urine pH:

Example: Cranberry juice acidifies urine, potentially affecting excretion of pH-sensitive drugs (though clinical significance debated).

Biliary Excretion:

Herbs inducing hepatic transporters (MRP2, BCRP) can increase biliary drug excretion.

Pharmacodynamic Interactions: Target-Level Effects

Pharmacodynamic interactions occur when herbs and drugs affect the same physiological targets, pathways, or organ systems.

Additive/Synergistic Effects

Mechanism: Herb + Drug both activate (or inhibit) the same pathway → combined effect exceeds individual effects.

Example 1: GABAergic Sedation

- GABA-A receptor: Primary inhibitory neurotransmitter receptor

- Drugs: Benzodiazepines (diazepam, alprazolam), zolpidem, barbiturates

- Herbs: Valerian (Valeriana officinalis), kava, passionflower, hops

Mechanism:

- Benzodiazepines bind allosteric site on GABA-A receptor → increase chloride channel opening frequency

- Valerian valerenic acid appears to modulate GABA-A receptor (exact mechanism debated)

- Kava kavalactones affect GABA-A receptor and voltage-gated sodium channels

Result: Enhanced CNS depression → excessive sedation, impaired coordination, respiratory depression (in severe cases)

Clinical relevance: Moderate. Most reports are case-level. The combination isn’t absolutely contraindicated but requires caution.

Example 2: Antiplatelet/Anticoagulant Effects

Coagulation cascade: Complex system with multiple targets for intervention.

Drugs:

- Warfarin: Vitamin K antagonist (inhibits factors II, VII, IX, X synthesis)

- Aspirin: Irreversibly inhibits COX-1 → reduced thromboxane A2 → reduced platelet aggregation

- Clopidogrel: P2Y12 ADP receptor antagonist → reduced platelet activation

- DOACs (rivaroxaban, apixaban): Direct factor Xa inhibitors

Herbs with antiplatelet/anticoagulant properties:

- Ginger (Zingiber officinale): Gingerols inhibit thromboxane synthetase and COX (dose-dependent, significant at >4g/day dried ginger)

- Garlic (Allium sativum): Allicin and ajoene inhibit platelet aggregation (dose-dependent, significant at >4g/day fresh garlic)

- Ginkgo biloba: Ginkgolides are PAF (platelet-activating factor) antagonists → reduced platelet aggregation

- Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium): Parthenolide inhibits platelet aggregation

- Turmeric (Curcuma longa): Curcumin inhibits platelet aggregation via multiple pathways (high doses required)

Result: Increased bleeding risk. Documented cases of spontaneous bleeding, increased INR, prolonged bleeding time.

Clinical significance: Varies by herb and dose:

- High risk: Ginkgo (multiple case reports of bleeding)

- Moderate risk: High-dose ginger, garlic, turmeric

- Low risk (culinary amounts): Normal food amounts of ginger, garlic, turmeric

Practical protocol:

- Stop high-dose anti-platelet herbs 1-2 weeks before surgery

- Monitor INR more frequently if using warfarin with these herbs

- Culinary amounts generally acceptable with monitoring

Antagonistic Effects

Mechanism: Herb and drug have opposing actions → reduced therapeutic effect.

Example: Immunosuppressants + Immune Stimulants

Drugs: Cyclosporine, tacrolimus, azathioprine, methotrexate

Purpose: Suppress immune system (transplant rejection, autoimmune disease)

Herbs: Echinacea, astragalus, medicinal mushrooms (reishi, maitake)

Effect: Stimulate immune system (increase T-cell, NK cell, macrophage activity)

Concern: Immune stimulation could:

- Counteract immunosuppression → transplant rejection risk

- Exacerbate autoimmune conditions

Evidence level: Theoretical concern based on mechanisms. Limited clinical case reports. Conservative approach warranted given severity of potential outcomes (organ rejection).

Recommendation: Avoid immune-stimulating herbs when taking immunosuppressants.

Serotonin Syndrome Risk

Mechanism: Excessive serotonergic activity at 5-HT receptors in CNS and periphery.

Classic triad: Altered mental status, autonomic hyperactivity, neuromuscular abnormalities

Symptoms: Confusion, agitation, restlessness, rapid heart rate, high blood pressure, dilated pupils, muscle rigidity, tremor, hyperreflexia, hyperthermia. Severe: seizures, rhabdomyolysis, DIC, death.

Drugs increasing serotonin:

- SSRIs: Inhibit serotonin re-uptake (sertraline, fluoxetine, citalopram)

- SNRIs: Inhibit serotonin + norepinephrine re-uptake (venlafaxine, duloxetine)

- MAOIs: Inhibit monoamine oxidase (phenelzine) → reduced serotonin breakdown

- Tramadol: Weak serotonin re-uptake inhibitor + opioid

- Others: Linezolid, methylene blue

Herbs increasing serotonin:

- St John’s Wort: Hyperforin inhibits serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine re-uptake (triple re-uptake inhibitor)

- SAMe (S-adenosylmethionine): Methyl donor in neurotransmitter synthesis

- 5-HTP (5-hydroxytryptophan): Direct serotonin precursor

Result: Combining St John’s Wort with SSRIs can produce serotonin syndrome. Multiple case reports documented.

Critical point: St John’s Wort creates a paradox:

- Pharmacodynamic interaction: Increases serotonin (risk of serotonin syndrome)

- Pharmacokinetic interaction: Induces CYP enzymes, reducing SSRI levels (treatment failure)

Recommendation: Never combine St John’s Wort with antidepressants.

Critical High-Risk Herbs

St John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): The Major Offender

Active constituents: Hypericin, hyperforin, flavonoids

Interaction mechanisms:

- Enzyme induction: CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP1A2, UGT1A1 (via PXR activation)

- Transporter induction: P-gp, MRP1 (multidrug resistance protein)

- Neurotransmitter re-uptake inhibition: Serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine (via hyperforin)

Documented major interactions:

| Drug Class | Specific Drug | Effect | Clinical Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunosuppressants | Cyclosporine, tacrolimus | ↓ AUC 46-62% | Transplant rejection (documented cases) |

| Antiretrovirals | Indinavir, efavirenz | ↓ AUC 57-81% | HIV treatment failure |

| Oral contraceptives | Ethinyl estradiol | ↓ AUC 13-15% | Breakthrough bleeding, unintended pregnancy |

| Anticoagulants | Warfarin | ↓ INR | Thrombosis risk |

| Anticancer | Imatinib, irinotecan | ↓ levels 30-40% | Treatment failure |

| Cardiac | Digoxin, ivabradine | ↓ levels 25-33% | Loss of therapeutic effect |

| Antidepressants | SSRIs, TCAs | Variable (↓ levels + ↑ serotonin) | Serotonin syndrome or treatment failure |

Dose-dependency: Hyperforin content determines interaction severity:

- <1mg/day hyperforin: Minimal interaction risk

- 1-5mg/day: Moderate interaction risk

- >5mg/day: High interaction risk

Standard extract: LI-160 contains ~5mg hyperforin per daily dose (900mg total extract).

Time course:

- Onset: 3-7 days

- Maximum: 10-14 days

- Resolution: 1-2 weeks after discontinuation

Conservative recommendation: Avoid St John’s Wort if taking any prescription medication.

Grapefruit Juice (Citrus × paradisi): CYP3A4 Inhibitor

Active constituents: Furanocoumarins (bergamottin, 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin)

Mechanism: Irreversible intestinal (not hepatic) CYP3A4 inhibition → increased drug bioavailability for drugs with high first-pass metabolism.

Timeline: Single glass (200mL) inhibits intestinal CYP3A4 for 24-72 hours.

Major interactions:

| Drug | Mechanism | Magnitude | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simvastatin, lovastatin | High first-pass CYP3A4 metabolism | ↑ AUC up to 16-fold | Rhabdomyolysis (documented deaths) |

| Felodipine, nifedipine | High first-pass CYP3A4 metabolism | ↑ AUC 2-4 fold | Severe hypotension, headache |

| Cyclosporine | CYP3A4 substrate | ↑ levels 50-200% | Nephrotoxicity risk |

| Buspirone | High first-pass metabolism | ↑ AUC 9-fold | Excessive sedation |

Important: Grapefruit affects drugs taken orally (not IV). Effect is intestinal, not systemic hepatic.

Alternative citrus:

- Safe: Oranges, lemons, limes (no significant furanocoumarins)

- Potentially problematic: Seville oranges (marmalade), pomelo, tangelos (contain furanocoumarins)

Ginkgo biloba: Bleeding Risk

Active constituents: Ginkgolides (terpenoids), bilobalide, flavonoids

Mechanisms:

- PAF antagonism: Ginkgolides are platelet-activating factor (PAF) receptor antagonists → reduced platelet aggregation

- Fibrinolytic activity: May enhance fibrinolysis

- Potential CYP2C19 inhibition: Unclear clinical significance

Documented bleeding events:

- Spontaneous hyphema (bleeding in eye)

- Subdural hematoma

- Intracerebral hemorrhage

- Post-operative bleeding

Evidence level: Multiple case reports but causality sometimes unclear (patients often on other anticoagulants).

Risk factors:

- Concurrent anticoagulant/antiplatelet drugs

- Pre-operative use

- High doses (>120-240mg/day extract)

Recommendation:

- Discontinue 1-2 weeks before surgery

- Avoid with warfarin, aspirin, clopidogrel unless closely monitored

- Caution in elderly (increased intracerebral bleeding risk)

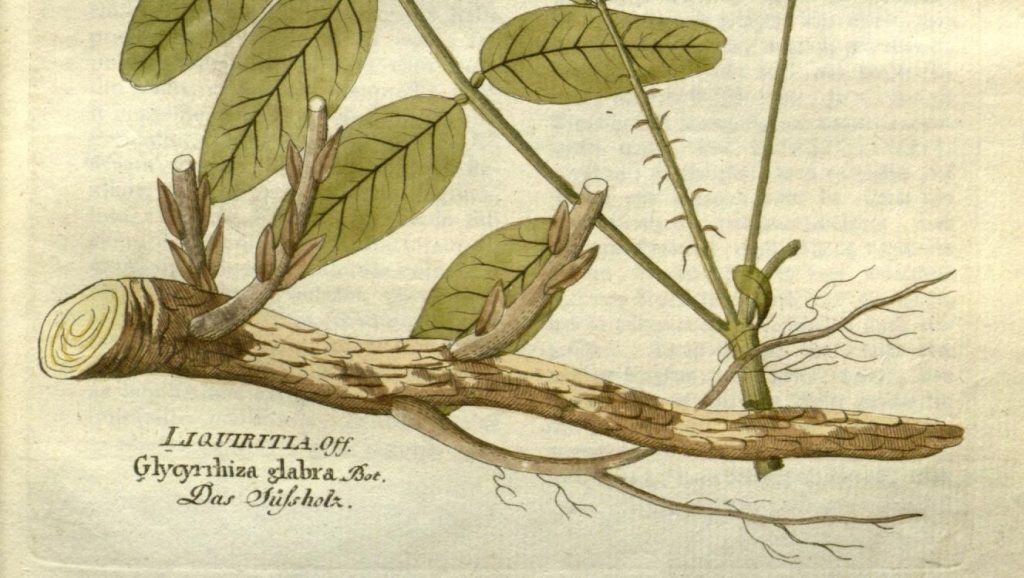

Liquorice Root (Glycyrrhiza glabra): Pseudoaldosteronism

Active constituent: Glycyrrhizin (glycyrrhizic acid)

Mechanism:

- Glycyrrhizin inhibits 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11β-HSD2)

- This enzyme normally converts cortisol → cortisone (inactive) in kidney

- Inhibition → cortisol accumulates in kidney

- Cortisol activates mineralocorticoid receptors (normally respond to aldosterone)

- Result: Sodium retention, potassium loss, water retention, hypertension

Clinical syndrome: Pseudoaldosteronism

- Hypertension

- Hypokalemia (low potassium → muscle weakness, cardiac arrhythmias)

- Metabolic alkalosis

- Oedema

Drug interactions:

- Antihypertensives: Liquorice antagonises their effect

- Diuretics: Potassium-wasting diuretics + liquorice → severe hypokalemia

- Digoxin: Hypokalemia sensitises heart to digoxin → toxicity risk

Dose-dependency:

- <5g/day: Minimal risk in healthy adults

- 5-15g/day: Possible effects with long-term use

- >15g/day: High risk

Time course: Effects develop over days to weeks, resolve over days after stopping.

Recommendation: Avoid in hypertension, heart failure, kidney disease, concurrent diuretics. Monitor potassium if using therapeutically.

Medication-Specific Interaction Profiles

Warfarin: The Narrow Therapeutic Index Drug

Warfarin pharmacology:

- Mechanism: Vitamin K epoxide reductase inhibitor → reduces vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (II, VII, IX, X)

- Monitoring: INR (International Normalised Ratio). Target typically 2-3 for most indications.

- Therapeutic index: Narrow. INR <2 = clotting risk, INR >4 = bleeding risk.

Warfarin metabolism: Primarily CYP2C9 (90%), minor CYP3A4, CYP1A2.

Herb interactions affecting warfarin:

Pharmacokinetic:

- CYP2C9 induction: St John’s Wort → reduced warfarin levels → decreased INR → clotting risk

- CYP2C9 inhibition: Goldenseal (berberine) → increased warfarin levels → increased INR → bleeding risk (case reports limited)

Pharmacodynamic (additive anticoagulation):

- Anti-platelet herbs: Ginkgo, garlic, ginger, feverfew → additive bleeding risk

- Vitamin K-containing herbs: High-dose green tea, nettle, alfalfa → reduced warfarin effect (theoretical; requires very high doses)

Case report: Cranberry juice + warfarin:

Multiple case reports of increased INR, some resulting in fatal haemorrhage. Mechanism debated (possible CYP2C9 inhibition). FDA and UK MHRA issued warnings.

Clinical protocol for warfarin + herbs:

- Inform patient about ALL potential interactions

- Avoid herbs with known anti-platelet effects

- Monitor INR more frequently if any dietary change

- Maintain consistent intake (if consuming vitamin K-rich herbs, keep dose consistent)

- Stop herbal supplements 1-2 weeks before surgery

Statins: CYP3A4 Substrate Variability

Statin classes by metabolism:

High CYP3A4 metabolism (HIGH grapefruit interaction risk):

- Simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin

- Mechanism: Extensive first-pass metabolism

- Grapefruit effect: ↑ AUC 2-16 fold

- Risk: Rhabdomyolysis (muscle breakdown)

Low/no CYP3A4 metabolism (LOW grapefruit interaction risk):

- Rosuvastatin (minimal CYP metabolism, OATP uptake)

- Pravastatin (minimal CYP metabolism)

- Fluvastatin (CYP2C9 metabolism)

- Grapefruit effect: Minimal (<2-fold)

Clinical significance: A patient on rosuvastatin can consume grapefruit safely. A patient on simvastatin should avoid grapefruit entirely.

Herb interactions with statins:

- St John’s Wort + simvastatin: ↓ simvastatin AUC 50% → reduced cholesterol-lowering

- Red yeast rice: Contains naturally occurring lovastatin (monacolin K) → avoid combination with prescription statins (additive statin effect → myopathy risk)

- Milk thistle (silymarin): In vitro CYP3A4 inhibition; clinical significance unclear

Antidepressants: The Serotonin Syndrome Risk

SSRIs (selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors):

- Fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram

- Mechanism: Block serotonin transporter (SERT) → increased synaptic serotonin

- Metabolism: Variable CYP enzymes (fluoxetine/paroxetine CYP2D6, others multiple)

Herb interaction: St John’s Wort

Scenario 1: Adding St John’s Wort to stable SSRI

- Immediate risk (days 1-7): Serotonin syndrome (pharmacodynamic interaction from hyperforin’s serotonin re-uptake inhibition)

- Delayed risk (days 7-14): Treatment failure (pharmacokinetic interaction as CYP induction reduces SSRI levels)

Scenario 2: Stopping SSRI and starting St John’s Wort

- Requires washout period (fluoxetine: 5 weeks due to long half-life; others: 1-2 weeks)

- Without washout: Serotonin syndrome risk

Documented serotonin syndrome cases: Multiple case reports of St John’s Wort + SSRI. Presentations range from mild (tremor, sweating) to severe (hyperthermia, seizures).

MAOIs (monoamine oxidase inhibitors):

- Phenelzine, tranylcypromine (older, rarely prescribed due to dietary restrictions)

- Mechanism: Irreversibly inhibit MAO-A and MAO-B → reduced breakdown of serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine

Absolute contraindication: MAOIs + any serotonergic herb. Serotonin syndrome risk is extreme.

Other herbs affecting mood:

- SAMe: Increases serotonin synthesis → serotonin syndrome risk with SSRIs

- 5-HTP: Direct serotonin precursor → serotonin syndrome risk with SSRIs

- L-tryptophan: Serotonin precursor → similar concerns

Clinical recommendation: Never combine antidepressants with St John’s Wort, SAMe, or 5-HTP.

Clinical Assessment and Risk Prediction

Evidence Hierarchy for Herb-Drug Interactions

Level 1: Established clinical interaction (highest confidence)

- Multiple case reports + clinical studies showing interaction

- Examples: St John’s Wort + cyclosporine, grapefruit + simvastatin

Level 2: Probable interaction

- Case reports + plausible mechanism + in vitro data

- Examples: Ginkgo + warfarin bleeding events

Level 3: Possible interaction (theoretical)

- Mechanistic plausibility + in vitro data, but no clinical reports

- Examples: Milk thistle CYP3A4 inhibition (strong in vitro, weak clinical evidence)

Level 4: Unlikely interaction

- Weak mechanistic basis, negative clinical studies

- Examples: Many herbal teas at normal consumption levels

Critical point: Absence of clinical reports doesn’t mean absence of risk (publication bias, underreporting). Conservative approach warranted for narrow therapeutic index drugs.

In Vitro vs. In Vivo Translation Challenge

Why in vitro data doesn’t always predict clinical interactions:

- Concentration mismatch: In vitro studies often use herb concentrations (μM range) far exceeding achievable plasma concentrations (nM range)

- Bioavailability: Many herb constituents have poor oral bioavailability (extensive first-pass metabolism, poor absorption)

Example: Milk thistle (silymarin)

- In vitro: Potent CYP3A4 inhibitor (IC50 ~10-50 μM)

- In vivo: Silymarin bioavailability <1%, peak plasma concentrations <1 μM

- Clinical studies: No significant CYP3A4 inhibition at standard doses

- Conclusion: In vitro inhibition doesn’t translate to clinical significance

- Metabolite effects: Parent compound may not be the active form. Gut microbiome metabolism can activate or deactivate compounds.

Implication: In vitro screening identifies potential interactions but requires clinical validation.

Preparing for Your Healthcare Appointments

Information to Share with Your Doctor or Pharmacist:

When discussing your health, it’s helpful to provide your healthcare team with complete information about everything you’re taking. Consider preparing a list that includes:

All prescription medications (name, dose, and how often you take them)

- Over-the-counter medications you use regularly

- Herbal products, vitamins, or supplements (including herbal teas)

- When you started each herb or supplement

- The exact dose you’re taking (in mg per day, not just “one capsule” – check the product label)

- Any changes in how you’ve been feeling since starting herbs or supplements

- Any upcoming surgeries or procedures you have scheduled

Symptoms Worth Mentioning:

Let your healthcare provider know if you’ve experienced any of these, especially after starting a new herb or supplement:

Unexpected changes in how well your medications seem to be working

- New or unusual bleeding or bruising

- Any new symptoms that started within 2 weeks of beginning an herbal product

- If you have regular blood tests (like INR for warfarin), any unexpected changes in your results

Working with Your Healthcare Team

Your Pharmacist Can Help:

New Zealand community pharmacists provide free medicines information services. They can:

Check for potential interactions between your medications and herbal products

- Explain how to take products safely

- Help you watch for signs of interactions

- Coordinate with your doctor when needed

Your Doctor Can Help:

Your doctor can review all your medications and supplements together to:

Adjust doses if needed

Arrange appropriate monitoring (blood tests, efficacy checks)

Refer you to specialists if required

Being Your Own Advocate:*

You know your body best. If something feels different after starting an herbal product alongside your medications, trust that instinct and speak up. Your healthcare team needs your observations to provide the best care.

New Zealand-Specific Considerations

Regulatory Framework

Medsafe (New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority):

- Regulates medicines (including complementary medicines)

- Classification: Prescription, Pharmacy-only, Restricted, General Sale

- Many herbal products fall under “General Sale” with minimal pre-market review

Natural Health Products Bill: Proposed regulatory framework (not yet enacted as of 2024). Would create mandatory product notification, GMP requirements, adverse event reporting.

Current reality: Variable product quality, limited regulatory oversight for complementary medicines.

Complementary Medicine Usage Patterns in NZ

Prevalence:

- ~40-50% of NZ adults use complementary medicines at least occasionally

- Higher in women, educated populations, chronic disease patients

- Māori and Pacific peoples may use traditional medicines (rongoā Māori) with distinct herb profiles

Common herbs used in NZ:

- St John’s Wort (depression, anxiety)

- Echinacea (immune support)

- Ginkgo biloba (cognitive enhancement, circulation)

- Garlic supplements (cardiovascular)

- Fish oil (cardiovascular, inflammation)

- Glucosamine/chondroitin (joint health)

- Kawakawa (Macropiper excelsum) – rongoā Māori

Rongoā Māori and Traditional Māori Medicine

Rongoā Māori as Complete Pharmacological System:

Rongoā Māori represents centuries of systematic empirical observation regarding New Zealand native plants, including sophisticated understanding of plant interactions, preparation methods that affect bioavailability, and integration with Western medications when patients use both systems.

Traditional Knowledge of Plant Interactions:

Māori traditional practitioners (tohunga rongoā) developed expertise in:

- Preparation-dependent effects: Traditional processing methods (heating, leaching, fermentation) alter phytochemical profiles and bioavailability

- Combination protocols: Which plants to combine and which to avoid—knowledge transmitted through cultural protocols

- Timing and dosing: Traditional understandings of therapeutic windows and interaction potential

- Individual assessment: Patient-specific factors in rongoā Māori may differ from Western pharmacokinetic considerations

Native NZ Plants with Potential Interactions:

Kawakawa (Macropiper excelsum):

- Constituents: Myristicin (phenylpropanoid, structurally related to safrole), elemicin, sesquiterpenes

- Traditional uses: Digestive complaints, skin conditions, urinary issues, analgesic

- Pharmacokinetic concerns:

- Myristicin theoretically may affect CYP enzymes (structurally similar to known CYP modulators)

- Limited clinical data on drug interactions

- Traditional preparation methods may affect constituent bioavailability

- Clinical approach: Conservative—monitor patients using kawakawa with narrow therapeutic index drugs

- Traditional contraindications: Pregnancy (respected in Western practice)

Manuka (Leptospermum scoparium):

- Constituents: Triketones (leptospermone), flavonoids, essential oils

- Uses: Antibacterial (honey), wound healing, digestive support

- Interaction potential: Unknown—no clinical studies on drug interactions

- Clinical approach: Generally low concern for interactions at culinary/therapeutic doses

Horopito (Pseudowintera colorata):

- Constituents: Polygodial (sesquiterpene dialdehyde—potent antifungal)

- Uses: Antifungal, digestive, respiratory

- Interaction potential: Unknown—theoretical interaction with antifungal medications (additive effects)

- Clinical approach: Monitor for enhanced antifungal effects if combined with conventional antifungals

Professional Boundaries and Collaborative Care:

Healthcare providers working in New Zealand should:

Acknowledge Limitations:

- Western pharmacology training does not confer expertise in rongoā Māori

- Rongoā Māori preparations may differ significantly from Western herbal supplements of same plant

- Traditional preparation methods affect phytochemical profiles in ways not captured by Western supplement analysis

Referral Pathways:

- Direct Māori patients seeking traditional approaches to qualified rongoā practitioners (tohunga rongoā)

- Hauora Māori services can facilitate connections to rongoā practitioners

- Collaborative care between rongoā practitioners and Western healthcare providers benefits patient safety

Respect Cultural Protocols:

- Some rongoā Māori knowledge is culturally protected (tapu) and not for public dissemination

- Traditional plant combinations and preparation methods are specialised knowledge

- Native plants are taonga (treasured) with cultural significance beyond pharmacology

Clinical Assessment Framework:

When patients use both rongoā Māori and Western medications:

- Ask specifically about rongoā Māori use (patients may not volunteer this information)

- Document rongoā use in medical records

- Consult with rongoā practitioner when possible (with patient consent)

- Apply conservative interaction assessment when clinical data unavailable

- Monitor drug levels, efficacy markers, adverse effects more closely

- Respect patient autonomy in choosing healing modalities

Research Gaps:

Significant research needed on:

- Pharmacokinetic properties of rongoā Māori preparations

- Drug interaction potential of commonly used native plants

- Effects of traditional preparation methods on bioavailability

- Pharmacogenomic considerations in Māori populations

- Cultural protocols for ethical research collaboration

Resources for Healthcare Providers:

- Rongoā practitioners: Qualified tohunga rongoā for traditional expertise

- Hauora Māori services: Māori health providers integrating both systems

- Research: Brooker, Cambie & Cooper (1987) New Zealand Medicinal Plants (documents traditional uses—not authorisation for practice)

- Research: Riley (1994) Māori Healing and Herbal (ethnobotanical documentation)

Critical Principle for Deep Dive Understanding:

This guide provides Western pharmacological and toxicological perspectives on herb-drug interactions. Rongoā Māori represents an equally sophisticated knowledge system with its own evidence base, diagnostic frameworks, therapeutic protocols, and safety knowledge developed over centuries. The two systems are complementary but not interchangeable.

When working with Māori patients or patients using rongoā Māori:

- Do not assume Western herb-drug interaction data applies to rongoā preparations

- Do not extract rongoā Māori knowledge for application outside its cultural context

- Do facilitate collaborative care between systems when clinically appropriate

- Do respect that rongoā Māori is complete healing system requiring its own expertise

Kawakawa Clinical Summary for Prescribers:

Given kawakawa’s increasing use and limited interaction data:

- Low concern: Typical traditional doses for most medications

- Moderate concern: Narrow therapeutic index drugs (warfarin, digoxin, lithium, immunosuppressants)—monitor more closely

- Pregnancy: Follow traditional contraindication—avoid use

- Approach: Document use, monitor drug efficacy/levels, engage collaborative care when possible

Resources Available in NZ

National Poisons Centre: 0800 764 766 (24/7)

- Emergency poisoning information

- Can advise on herb-drug interactions in acute situations

Medsafe: www.medsafe.govt.nz

- Medicine safety information

- Adverse reaction reporting (CARM – Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring)

Pharmacist consultation:

- Free service at community pharmacies

- Interaction database access

Medical herbalists:

- NZAMH (NZ Association of Medical Herbalists) members maintain professional standards

- Can provide evidence-based herbal consultations

Evidence Levels and Research Limitations

The Evidence Gap

Current state:

- Well-studied interactions: <20 herbs (St John’s Wort, ginkgo, ginseng, garlic, echinacea, grapefruit, cranberry, green tea, kava, valerian)

- Clinically used herbs: >500 species worldwide

- Mechanistic data: Mostly in vitro, limited in vivo

- Clinical trials: Few randomised controlled trials (expensive, lack of funding)

Publication bias:

- Positive interaction findings more likely published than negative findings

- Case reports more likely for dramatic adverse events

- Routine safe co-administration underreported

Challenges in Herb-Drug Interaction Research

Herb variability:

- Different species (Panax ginseng vs. Panax quinquefolius)

- Different plant parts (root vs. leaf)

- Different extraction methods (water vs. alcohol vs. CO2)

- Different commercial preparations (standardisation vs. crude)

- Batch-to-batch variation

Example: Ginseng studies show conflicting results partly because “ginseng” refers to multiple species, parts, and preparations with different ginsenoside profiles.

Methodological issues:

- Dose: Clinical studies often use arbitrarily chosen doses, not reflecting real-world usage

- Duration: Short-term studies may miss delayed effects (enzyme induction takes days)

- Healthy volunteer bias: Interaction magnitude may differ in patient populations

- Outcome measures: Surrogate markers (drug levels) vs. clinical outcomes (bleeding events)

Interpreting Contradictory Evidence

When studies conflict:

Example: Milk thistle + cyclosporine

- In vitro: Strong CYP3A4 inhibition, P-gp inhibition

- Clinical study 1: No interaction (Piscitelli 2002, silymarin 160mg 3x/day × 28 days)

- Clinical study 2: Small increase in cyclosporine trough (Brants 2004)

- Conclusion: Likely low clinical significance at standard doses

Factors explaining discrepancies:

- Herb preparation differences

- Patient genetics (CYP polymorphisms)

- Study power (small studies miss small effects)

- Timing of sampling

Conservative approach: For narrow therapeutic index drugs, err on side of caution even with conflicting evidence.

Future Directions

Needed research:

- Population pharmacokinetic studies (account for individual variability)

- Long-term safety monitoring (post-market surveillance)

- Genetic factors (CYP polymorphisms, transporter polymorphisms)

- Herb-herb-drug interactions (poly-herbal formulas)

- Food-herb-drug interactions

- Microbiome effects on herb and drug metabolism

Emerging tools:

- Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling: Computer simulations predicting interactions

- Pharmacometabolomics: Identifying biomarkers of herb exposure and effect

- Machine learning: Predicting interaction risk from chemical structure and known data

Conclusion: Practical Integration

The Core Principles

- Communication is paramount: Patients must disclose all herb use; providers must ask non-judgmentally.

- Risk stratification matters: Not all herb-drug combinations are equally risky. Narrow therapeutic index drugs require intensive screening.

- Evidence-based but cautious: Use available evidence, but recognise its limitations. Conservative approach for high-stakes situations.

- Individual variability: Genetics, age, disease state, and concurrent medications all affect interaction risk.

- Timing matters (sometimes): Some interactions can be mitigated by separating administration times; others cannot.

Clinical Decision Framework

For each patient taking medications + herbs:

Step 1: Inventory

- Complete medication list (Rx, OTC, herbs, supplements)

- Doses, frequencies, duration of use

Step 2: Risk Assessment

- Narrow therapeutic index drugs? (yes → high risk)

- Known interacting herbs? (St John’s Wort, ginkgo → high risk)

- Polypharmacy? (≥5 drugs → increased risk)

Step 3: Mechanism Analysis

- Pharmacokinetic concern (CYP, P-gp)?

- Pharmacodynamic concern (additive effects)?

Step 4: Evidence Review

- Check interaction databases (Natural Medicines Database, Micromedex)

- Review primary literature for high-risk combinations

Step 5: Management Plan

- Avoid: High-risk combinations (St John’s Wort + most Rx)

- Monitor: Moderate-risk combinations (frequent labs, assess symptoms)

- Educate: Inform patient of warning signs

- Document: Record herb use in medical record

Step 6: Follow-up

- Reassess at every visit

- Monitor drug levels, efficacy markers, adverse effects

The Balanced Perspective

Herbs are not inherently dangerous, but they are not inherently safe either. They contain bioactive compounds that interact with the body—and therefore can interact with medications.

The goal is not herb avoidance, but informed, safe co-administration when appropriate.

Most interactions are manageable with:

- Awareness

- Communication

- Monitoring

- Dose adjustment

- Or simply avoiding the few truly high-risk combinations

Final thought: Herb-drug interactions are a clinical reality requiring evidence-based assessment, not fear-based prohibition. With proper knowledge and communication, the vast majority of patients can safely integrate herbal and pharmaceutical medicine.

References

Comprehensive bibliography of herb-drug interaction research:

Foundational Reviews and Textbooks:

Williamson, E. M., Driver, S., & Baxter, K. (Eds.). (2013). Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions (2nd ed.). Pharmaceutical Press, London.

[Definitive professional reference—comprehensive interaction monographs]

Bone, K., & Mills, S. (2013). Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

[Comprehensive herbal pharmacology including drug interactions and clinical applications]

Izzo, A. A., & Ernst, E. (2009). Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: an updated systematic review. Drugs, 69(13), 1777-1798. https://doi.org/10.2165/11317010-000000000-00000

[Systematic review of clinical evidence for herb-drug interactions]

St John’s Wort—CYP450 Induction:

Zhou, S., Chan, E., Pan, S. Q., Huang, M., & Lee, E. J. (2004). Pharmacokinetic interactions of drugs with St John’s wort. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 18(2), 262-276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881104042632

[Comprehensive review of St John’s Wort CYP3A4 induction mechanisms and clinical consequences]

Henderson, L., Yue, Q. Y., Bergquist, C., Gerden, B., & Arlett, P. (2002). St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): drug interactions and clinical outcomes. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 54(4), 349-356. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01683.x

[Clinical case reports of St John’s Wort interactions with cyclosporine, oral contraceptives, others]

Wang, L. S., Zhou, G., Zhu, B., et al. (2004). St John’s wort induces both cytochrome P450 3A4-catalysed sulfoxidation and 2C19-dependent hydroxylation of omeprazole. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 75(3), 191-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clpt.2003.11.011

[CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 induction by St John’s Wort]

Grapefruit—CYP3A4 Inhibition:

Bailey, D. G., Dresser, G., & Arnold, J. M. (2013). Grapefruit-medication interactions: forbidden fruit or avoidable consequences? Canadian Medical Association Journal, 185(4), 309-316. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.120951

[Comprehensive review of grapefruit furanocoumarin mechanism-based CYP3A4 inhibition]

Bailey, D. G., Malcolm, J., Arnold, O., & Spence, J. D. (1998). Grapefruit juice-drug interactions. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 46(2), 101-110. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00764.x

[Classic paper establishing grapefruit-drug interaction mechanisms]

Anticoagulant/Antiplatelet Interactions:

Ulbricht, C., Chao, W., Costa, D., et al. (2008). Clinical evidence of herb-drug interactions: a systematic review by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. Current Drug Metabolism, 9(10), 1063-1120. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920008786485074

[Systematic review including anticoagulant herb interactions—ginger, garlic, ginkgo, feverfew]

Jiang, X., Williams, K. M., Liauw, W. S., et al. (2005). Effect of ginkgo and ginger on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 59(4), 425-432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02322.x

[Clinical trial showing no significant warfarin interaction at tested doses]

P-glycoprotein Interactions:

Zhou, S., Lim, L. Y., & Chowbay, B. (2004). Herbal modulation of P-glycoprotein. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 36(1), 57-104. https://doi.org/10.1081/DMR-120028427

[Comprehensive review of P-glycoprotein herb interactions including St John’s Wort]

Pharmacodynamic Interactions:

Ang-Lee, M. K., Moss, J., & Yuan, C. S. (2001). Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA, 286(2), 208-216. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.2.208

[Clinical review of herb-anaesthesia interactions and perioperative herb management]

Evidence Quality and Research Methods:

Chen, X. W., Sneed, K. B., Pan, S. Y., et al. (2012). Herb-drug interactions and mechanistic and clinical considerations. Current Drug Metabolism, 13(5), 640-651. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200211209050640

[Review of interaction mechanisms, research methodologies, evidence quality assessment]

Gurley, B. J., Gardner, S. F., Hubbard, M. A., et al. (2005). In vivo effects of goldenseal, kava kava, black cohosh, and valerian on human cytochrome P450 1A2, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4/5 phenotypes. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 77(5), 415-426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clpt.2005.01.009

[Clinical phenotyping study of herb CYP effects]

Immunosuppressant Interactions:

Piscitelli, S. C., Formentini, E., Burstein, A. H., Alfaro, R., Jagannatha, S., & Falloon, J. (2002). Effect of milk thistle on the pharmacokinetics of indinavir in healthy volunteers. Pharmacotherapy, 22(5), 551-556. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.22.7.551.33666

[Clinical trial showing no indinavir interaction with milk thistle]

NZ-Specific and Rongoā Māori:

Brooker, S. G., Cambie, R. C., & Cooper, R. C. (1987). New Zealand Medicinal Plants. Heinemann, Auckland.

[Ethnobotanical documentation of rongoā Māori and European settler plant medicine—historical reference]

Riley, M. (1994). Māori Healing and Herbal: New Zealand Ethnobotanical Sourcebook. Viking Sevenseas NZ Ltd.

[Scholarly compilation of traditional Māori plant knowledge]

Pledger, M., Cumming, J., & Burnette, M. (2010). Health service use amongst users of complementary and alternative medicine. New Zealand Medical Journal, 123(1312), 26-35.

[NZ-specific data on complementary medicine usage patterns]

Clinical Guidelines:

Natural Medicines Database. TRC Healthcare. Available at: https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com

[Subscription database—frequently updated herb-drug interaction monographs]

Micromedex. IBM Watson Health. Available at: http://www.micromedexsolutions.com

[Clinical interaction database used by healthcare providers]

New Zealand Formulary (NZF). Available at: https://nzformulary.org/

[NZ medication reference including some herb-drug interaction information]

Disclaimer: This guide is for educational and professional reference purposes only. It provides evidence-based information on herb-drug interactions but does not constitute medical advice, clinical guidelines, or standard of care. Individual patient management requires clinical judgment considering specific medications, doses, co-morbidities, pharmacogenomic factors, and patient-specific variables. Always consult with qualified healthcare professionals for personalised clinical recommendations.

This guide covers herb-drug interactions from Western pharmacological perspectives and is not a substitute for traditional indigenous knowledge systems including rongoā Māori. Rongoā Māori has its own frameworks for understanding plant interactions and safe integration with Western medications. For rongoā Māori approaches, refer to qualified rongoā practitioners (tohunga rongoā). Western healthcare providers should not assume rongoā Māori preparations have identical interaction profiles to Western herbal supplements.

The interaction information represents current scientific understanding based on available research, but significant evidence gaps exist. Individual responses to herb-drug combinations vary due to genetic polymorphisms (CYP450 variants, transporter polymorphisms), disease states, age, sex, and concurrent medications. Not all herb-drug combinations have been studied—absence of published interaction data does not indicate safety. For narrow therapeutic index drugs and critical medications (immunosuppressants, anticoagulants, chemotherapy, transplant drugs), apply conservative precautionary principle even when interaction data are limited.

Healthcare providers should maintain appropriate professional indemnity insurance, follow all Medsafe regulations, report serious adverse reactions to CARM (Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring), and work within their scope of practice. This guide does not establish standard of care and should not replace clinical guidelines, poison control consultation (National Poisons Centre: 0800 764 766), specialist advice, or medication package inserts. Children under 2 years should not receive herbal preparations without specialist paediatric guidance.

The authors and publisher assume no liability for adverse reactions, drug interactions, clinical decisions, misidentifications, or treatment complications arising from use of this information. Herb-drug interaction assessment requires integration of multiple data sources, clinical experience, and patient-specific factors. When in doubt, consult the National Poisons Centre (0800 764 766), pharmacist, or specialist.