A Scientific Analysis of Pitfalls, Mechanisms, and Evidence-Based Solutions

Introduction & Scope

This comprehensive guide examines frequent errors in herbal medicine preparation and use through clinical, botanical, pharmaceutical, and toxicological lenses. We deconstruct why these mistakes occur, their potential consequences ranging from inefficacy to toxicity, and establish evidence-based protocols to prevent them. This analysis is essential for serious students of herbalism, healthcare practitioners integrating botanical medicine, and anyone committed to safe, effective herbal practice.

Table of Contents

- Botanical Identification Errors

- Formulation and Synergy Mistakes

- Preparation and Processing Errors

- Storage and Stability Issues

- Dosing and Pharmacokinetic Errors

- Safety, Toxicology, and Contraindications

- Quality Control and Contamination

- Methodological Selection Errors

- Expectation and Timeline Mismanagement

- Documentation and Standardisation

1. Botanical Identification Errors

The Critical Nature of Accurate Identification

Plant misidentification represents the single most dangerous error in herbal medicine, with documented fatalities occurring annually worldwide from consumption of toxic plants mistaken for medicinal or edible species.

Case Studies of Fatal Misidentification

Conium maculatum (Hemlock) Toxicity:

According to Froberg et al. (2007), there are over 100,000 toxic plant exposure reports to poison centres in the United States annually, with the most serious cases involving adults who mistook poisonous plants for edible species. Hemlock (Conium maculatum), containing piperidine alkaloids (coniine, γ-coniceine), is frequently misidentified as:

- Wild carrot (Daucus carota)

- Wild parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris)

- Wild chervil (Chaerophyllum spp.)

Mechanism of Hemlock Toxicity:

Piperidine alkaloids function as nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists at neuromuscular junctions, initially stimulating then blocking neurotransmission (Vetter, 2004). This produces ascending muscular paralysis, culminating in respiratory failure. The lethal dose for an adult is approximately 100-150 mg of coniine (contained in ~6-8 leaves or less plant material).

Identification Protocol Failures:

Single-Feature Reliance:

Novice foragers frequently rely on a single morphological characteristic:

- Leaf shape alone (insufficient — many Apiaceae species share pinnately compound leaves)

- Flower colour (white umbels common to dozens of species)

- Habitat (hemlock grows in diverse environments)

Correct Identification Requires Multiple Characteristics:

- Stem morphology: Conium maculatum has hollow, hairless stems with distinctive purple or reddish blotches

- Leaf arrangement: Triangular outline, finely divided (2-4 pinnate)

- Odour: Crushed foliage produces pungent “mousey” or rank smell

- Root structure: White taproot, parsnip-like

- Habitat context: Waste ground, roadsides, stream banks

- Size: Typically 1.5-2.5 metres tall

Compare with Wild Carrot (Daucus carota):

- Hairy stems (no purple blotches)

- Carroty smell when crushed

- Often has single purple floret in centre of white flower cluster

- Produces edible taproot (orange when cultivated, white when wild)

Taxonomic Complexity and Look-Alikes

The Asteraceae Problem:

Within the Asteraceae (Compositae) family, several genera contain both medicinal and toxic species:

Arnica montana vs. Inula helenium:

Both have yellow composite flowers, but:

- Arnica: Primarily topical use, internal use limited due to hepatotoxicity from helenalin content

- Inula (Elecampane): Safe internal use for respiratory conditions, contains inulin and alantolactone

Senecio spp. (Ragwort) Toxicity:

Contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) causing hepatic veno-occlusive disease. Chronic exposure leads to cirrhosis. Critical to distinguish from:

- Tanacetum vulgare (Tansy)

- Solidago spp. (Goldenrod)

- Other yellow composite flowers

Scientific Identification Methodology

Dichotomous Keys:

Employ systematic keys that present paired morphological choices based on multiple characteristics. Example key structure:

1a. Leaves opposite → Go to 2

1b. Leaves alternate → Go to 5

2a. Stem square → Lamiaceae family likely

2b. Stem round → Go to 3

[continues with increasing specificity]

Voucher Specimen Protocol:

Professional herbalists and researchers create voucher specimens:

- Collect representative sample including roots, stems, leaves, flowers, fruits (where ethically possible)

- Press and dry between newspaper/blotting paper

- Mount on archival paper with label including:

- Collection location (GPS coordinates)

- Date

- Habitat description

- Preliminary identification

- Compare with authenticated herbarium specimens

- Seek expert verification from botanist or herbarium curator

Molecular Verification (Advanced):

DNA barcoding using regions like ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) or matK provides definitive identification, particularly valuable for:

- Processed/dried materials where morphology is obscured

- Species complexes with minimal morphological distinction

- Quality control of commercial herbal products

New Zealand-Specific Identification Challenges

Native Species Conservation Status:

Many native NZ medicinal plants are threatened or at risk. The NZ Plant Conservation Network (www.nzpcn.org.nz) provides conservation status:

- Nationally Critical: e.g., Dactylanthus taylorii (wood rose) — do not harvest

- Nationally Endangered: Multiple species — requires expert permission

- At Risk — Declining: Many traditionally used species — harvest minimally if at all

Introduced Toxic Species Common in NZ:

- Digitalis purpurea (Foxglove): Cardiac glycosides (digitoxin)

- Atropa belladonna (Deadly nightshade): Tropane alkaloids

- Conium maculatum (Hemlock): As above

- Coriaria spp. (Tutu): Tutin (picrotoxin-like)

Prevention Protocol: The Triple-Verification System

Step 1: Field Identification

- Use minimum of two field guides with photographic keys

- Document multiple morphological features

- Photograph plant from multiple angles

- Note habitat, associated species, season

Step 2: Laboratory/Home Verification

- Compare fresh specimen with multiple botanical references

- Consult NZ-specific flora guides (Flora of New Zealand, Crowe botanical guides)

- Use hand lens to examine minute features (hairs, glands, flower structure)

Step 3: Expert Confirmation

- Submit photos to local herbarium or botanical society

- Consult experienced local forager or botanist

- Participate in plant identification walks led by experts

- When in doubt, submit voucher specimen to herbarium

Never proceed to consumption or preparation without 100% certainty.

2. Formulation and Synergy Mistakes

The Polypharmacy Trap

Definition: Combining numerous herbs (5-15+ species) without understanding their individual or combined actions, pharmacokinetics, or potential interactions.

Phytochemical Complexity

Each herb contains 200-1000+ distinct chemical compounds. A 10-herb formula potentially contains 2,000-10,000 compounds. The combinatorial complexity makes predicting effects nearly impossible.

Synergy vs. Antagonism vs. Additive Effects

Synergy (1+1=3):

Two compounds enhance each other’s effects beyond simple addition.

Example: Piperine + Curcumin

Piperine (from Piper nigrum) inhibits hepatic and intestinal glucuronidation of curcumin, increasing bioavailability 2000% (Shoba et al., 1998).

Mechanism:

- Curcumin undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism via UDP-glucuronosyltransferases

- Piperine competitively inhibits these enzymes

- More free curcumin remains bioavailable

Antagonism (1+1=0):

Two compounds oppose each other’s actions.

Example: Caffeine + Valerian

Caffeine (adenosine receptor antagonist, CNS stimulant) vs. Valerian (GABAergic, CNS depressant) produce opposing effects, potentially canceling benefits of both.

Additive Effects (1+1=2):

Two compounds with similar mechanisms produce cumulative effects.

Example: Multiple Sedative Herbs

Valerian (GABAergic) + Passionflower (GABAergic) + Kava (GABAergic) = Excessive sedation

Risk: When combined with pharmaceutical sedatives (benzodiazepines, zolpidem), can produce dangerous respiratory depression.

Clinical Implications of Complex Formulas

Impossibility of Determining Active Agent:

In a 10-herb formula, which herb (or compound) produced the beneficial effect? Which caused the side effect? This knowledge gap prevents:

- Dose optimisation

- Side effect management

- Formula refinement

- Reproducibility

Increased Interaction Risk:

Each additional herb increases potential for:

- Herb-drug interactions

- Herb-herb interactions

- Allergic reactions

- Unexpected synergies

Traditional Formulation Principles

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) Approach:

Structured hierarchical system:

Jun (Emperor/Chief) – 20-50% of formula:

- Primary therapeutic herb

- Addresses root pattern/main symptom

- Highest dose

Chen (Minister/Deputy) – 20-30%:

- Supports chief herb

- Addresses secondary symptoms

- Moderate dose

Zuo (Assistant) – 10-20%:

- Moderates harsh properties of chief

- Treats concurrent symptoms

- Lower dose

Shi (Envoy/Guide) – 5-10%:

- Harmonises formula

- Guides herbs to specific meridians

- Improves taste

- Lowest dose

Western Herbalism Traditional Approach:

Simpler but similar hierarchy:

Primary (60-80%): Main therapeutic herb

Supporting (20-30%): Enhances primary herb

Catalyst (5-10%): Improves absorption, flavour, or delivery

Evidence-Based Simplicity Protocol

Start with Monotherapy:

- Use single herb for minimum 2-4 weeks

- Document effects thoroughly:

- Beneficial effects (nature, timeline, intensity)

- Neutral effects

- Adverse effects (onset, severity, resolution)

- Establish baseline response

Two-Herb Combination (If Needed):

- Maintain primary herb (established as effective)

- Add single supporting herb

- Wait 1-2 weeks, reassess

- If improvement, maintain; if not, remove second herb

Three-Herb Maximum for Beginners:

- Chief herb (60%+)

- Supporting herb (30%)

- flavour or catalyst herb (10%)

Professional Formulation (Advanced):

Practitioners with extensive training may use 4-7 herb formulas, but:

- Each herb serves specific, understood function

- Interactions are known or researched

- Formula follows established traditional pattern with clinical evidence

- Individual herbs have been tested separately

Case Example: Digestive Bitters Formula

Poor Formulation (Too Complex):

Gentian + Dandelion + Burdock + Artichoke + Oregon Grape + Milk Thistle + Ginger + Fennel + Cardamom + Liquorice

Problems:

- 10 herbs, 1000+ compounds

- Overlapping bitters (redundant)

- Liquorice can mask other flavours

- Expensive, complex to prepare

- Can’t identify which herb helps

Evidence-Based Formulation:

Primary: Gentian root (60%) – Extremely bitter secoiridoid glycosides stimulate bitter taste receptors

Supporting: Ginger root (30%) – Warming carminative, aids motility

Catalyst: Orange peel (10%) – Improves flavour compliance, mild bitter

Why This Works:

- Each herb serves distinct function

- Gentian provides primary bitter stimulation

- Ginger addresses gas/bloating

- Orange makes it palatable

- If ineffective, easy to troubleshoot (increase gentian? Try different supporting herb?)

—

3. Preparation and Processing Errors

Moisture-Related Contamination

Microbial Growth Kinetics:

Mold, bacteria, and yeast require water activity (aw) for growth:

- aw > 0.85: Optimal for bacterial growth

- aw 0.75-0.85: Mold growth possible

- aw 0.60-0.75: Yeast growth possible

- aw < 0.60: Microbial growth inhibited

Fresh vs. Dried Herb Water Content:

- Fresh herbs: 70-90% water (aw ā 0.98)

- Properly dried herbs: 8-12% water (aw ā 0.4-0.6)

Critical Threshold: Herbs must be dried to <12% moisture content to prevent microbial proliferation.

Mycotoxin Production

Aflatoxins:

Produced by Aspergillus species growing on improperly dried herbs. Aflatoxins are:

- Hepatotoxic: Cause acute liver damage at high doses

- Carcinogenic: Classified as Group 1 carcinogen by IARC

- Heat-stable: Not destroyed by cooking or boiling

Prevention: Proper drying and storage in low-humidity environments.

Drying Science and Methodology

Optimal Drying Conditions:

- Temperature: 30-40°C for most herbs (preserves volatile oils and heat-sensitive compounds)

- Higher temperatures (50-60°C) acceptable for roots/bark but may degrade some compounds

- Humidity: <50% relative humidity

- Airflow: Strong circulation prevents surface moisture accumulation

Thermolabile Compound Considerations:

Volatile Oils:

Monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes (menthol, linalool, β-caryophyllene) evaporate at temperatures >50°C. Proper drying at 35-40°C preserves these compounds while removing water.

Example: Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis)

Contains citral, citronellal, geraniol (extremely volatile).

- Drying at >40°C: Significant volatile oil loss (up to 50-70%)

- Drying at 35°C with good airflow: Retains 80-90% of volatile oils

Enzymatic Activity During Drying:

Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO):

Catalyses oxidation of phenolic compounds (tannins, catechins) to quinones, producing browning and reduced antioxidant capacity.

Inhibition Strategy:

- Rapid drying (reduces time for enzymatic activity)

- Low temperature (reduces enzyme activity)

- Some traditions use brief blanching (95°C, 30 seconds) to denature enzymes before drying

Drying Method Comparison

Air Drying (Ambient Temperature):

- Advantages: No equipment cost, preserves heat-sensitive compounds

- Disadvantages: Slow (1-3 weeks), weather-dependent, mold risk in humid climates, significant volatile oil loss over extended period

- Best for: Roots, bark, seeds in dry climates

Dehydrator (Controlled Temperature):

- Advantages: Consistent temperature, rapid (4-24 hours), weather-independent, best volatile oil retention

- Disadvantages: Equipment cost ($50-300 NZD)

- Best for: Aromatic herbs, flowers, leaves

Oven Drying (Low Temperature):

- Advantages: Accessible (no special equipment)

- Disadvantages: Difficult temperature control (many ovens don’t go below 50°C), uneven drying, electricity cost

- Best for: Emergency drying of small quantities

Freeze Drying (Lyophilisation):

- Advantages: Superior preservation of all compounds, colour, and aroma

- Disadvantages: Expensive equipment ($2000-15,000 NZD), not accessible to home herbalists

- Best for: Commercial production of high-value herbs

Quality Assessment Post-Drying

Organoleptic Testing:

Visual:

- colour should be close to fresh (fading indicates degradation)

- No brown/black spots (mold or oxidation)

- No visible moisture

Tactile:

- Leaves should crumble easily

- Stems should snap, not bend

- No cool/damp feeling

Olfactory:

- Strong, characteristic aroma

- No musty, moldy, or off odors

Moisture Content Testing (Professional):

- Gravimetric method: Weigh sample, dry at 105°C for 24 hours, reweigh

- Moisture % = [(Initial weight – Dry weight) / Initial weight] × 100

- Target: <10-12%

4. Storage and Stability Issues

Degradation Pathways

Oxidation:

Chemical reaction between phytochemicals and atmospheric oxygen, producing degradation products.

Example: Hypericin in St. John’s Wort

Light exposure accelerates oxidation of hypericin (naphthodianthrone) to inactive compounds. Studies show 50% loss of hypericin after 6 months exposure to fluorescent light (Schempp et al., 2002).

Free Radical Chain Reaction:

Initiation: RH + O₂ → R• + •OOH

Propagation: R• + O₂ → ROO•

ROO• + RH → ROOH + R•

Termination: R• + R• → R-R

Where RH = phytochemical with hydrogen atom susceptible to abstraction.

Factors Accelerating Oxidation:

- Light (provides energy for reaction initiation)

- Heat (increases reaction kinetics)

- Presence of metals (Fe²⁺ Cu²⁺ act as catalysts)

- Air exposure (increased oxygen availability)

Hydrolysis:

Water-mediated breakdown of chemical bonds.

Example: Glycosides

Many medicinal compounds exist as glycosides (sugar-bound form). Water can hydrolyse the glycosidic bond:

Glycoside + H₂O → Aglycone + Sugar

This may increase or decrease activity depending on compound.

Volatile Oil Evaporation:

Essential oils (monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes) have low boiling points and vapour pressures, causing gradual loss to atmosphere even in closed containers.

Example: Valerian Root

Valerenic acid and volatile oils decline 30-50% after 12 months storage at room temperature even in sealed containers (Houghton, 1999).

Container Material Science

Glass:

- Inert: No chemical reaction with herbal constituents

- Impermeable: Doesn’t allow oxygen or moisture transmission (if properly sealed)

- Drawback: Transparent glass allows light penetration

Amber/Cobalt Glass:

- Filters UV light (wavelengths <450 nm)

- Reduces photodegradation by 80-95%

Plastic (HDPE, PET):

- Problems:

- Permeable to oxygen (allows oxidation)

- Can leach chemicals (plasticisers, stabilisers) into herbs, especially with volatile oils

- Static electricity attracts fine herb particles

- Avoid for long-term storage

Metal Tins:

- Good: Opaque, air-resistant when sealed

- Problem: Can react with tannins and acidic compounds

- Best for: Short-term storage of salves, balms

Optimal Storage Conditions by Preparation Type

Dried Herbs:

- Temperature: 15-20°C (cool room temperature)

- Light: Complete darkness (opaque container in cupboard)

- Humidity: <50% RH

- Container: Glass jar, filled to minimise air space, tight lid

- Expected shelf life:

- Leaves/flowers (aromatic): 6-12 months

- Leaves/flowers (non-aromatic): 12-18 months

- Roots/bark: 2-3 years

- Seeds: 2-3 years

Tinctures (>40% Alcohol):

- Temperature: 15-25°C (room temperature acceptable)

- Light: Dark glass bottle

- Container: Dropper bottles or bottles with tight caps

- Expected shelf life: 3-5+ years (alcohol is preservative)

Infused Oils:

- Temperature: 15-20°C (cool cupboard, refrigeration optional for very unstable oils)

- Light: Dark glass, complete darkness

- Air: Fill bottles completely (minimal headspace)

- Antioxidant: Add vitamin E (α-tocopherol) 0.1% w/w

- Expected shelf life:

- Jojoba: 2+ years

- Olive: 12-18 months

- Sweet almond: 6-12 months

- Sunflower: 3-6 months

Rancidity Chemistry:

Lipid peroxidation proceeds via free radical mechanism:

Initiation: LH (lipid) + •OH → L• + H₂O

Propagation: L• + O₂ → LOO•

LOO• + LH → LOOH + L•

Termination: Antioxidants (vitamin E) donate H• to LOO•, terminating chain

Peroxide Value (PV): Measure of lipid oxidation state

- Fresh oil: PV <5 mEq/kg

- Rancid oil: PV >20 mEq/kg

Salves/Balms:

- Temperature: 15-25°C (refrigeration extends shelf life but not necessary)

- Container: Tins or jars with tight lids

- Expected shelf life: 12-18 months (depends on oil stability)

Syrups:

- Temperature: Refrigerate after opening (4-8°C)

- Preservation: High sugar content (60%+ w/w) inhibits microbial growth

- Expected shelf life: Unopened 6-12 months; opened 2-3 months refrigerated

Stability Testing Protocol

Home Herbalist Monitoring:

Monthly Checks (First 3 Months):

- Visual inspection for mold, discoloration, separation

- Olfactory check for off-odors

- Note any changes in appearance

Quarterly Checks (After Initial 3 Months):

- Same parameters

- Consider re-making if significant degradation observed

Professional/Commercial Stability Testing:

- Accelerated aging: Store at elevated temperature (40°C) and humidity (75% RH)

- Chemical analysis: HPLC quantification of marker compounds at 0, 3, 6, 12 months

- Microbial testing: Total aerobic count, yeast/mold count

- Determine shelf life based on when marker compounds fall below 90% of initial concentration

5. Dosing and Pharmacokinetic Errors

The Dose-Response Relationship

Hormesis:

Many herbal compounds exhibit biphasic dose-response curves:

- Low dose: Beneficial (stimulatory)

- Moderate dose: Optimal therapeutic

- High dose: Harmful (inhibitory or toxic)

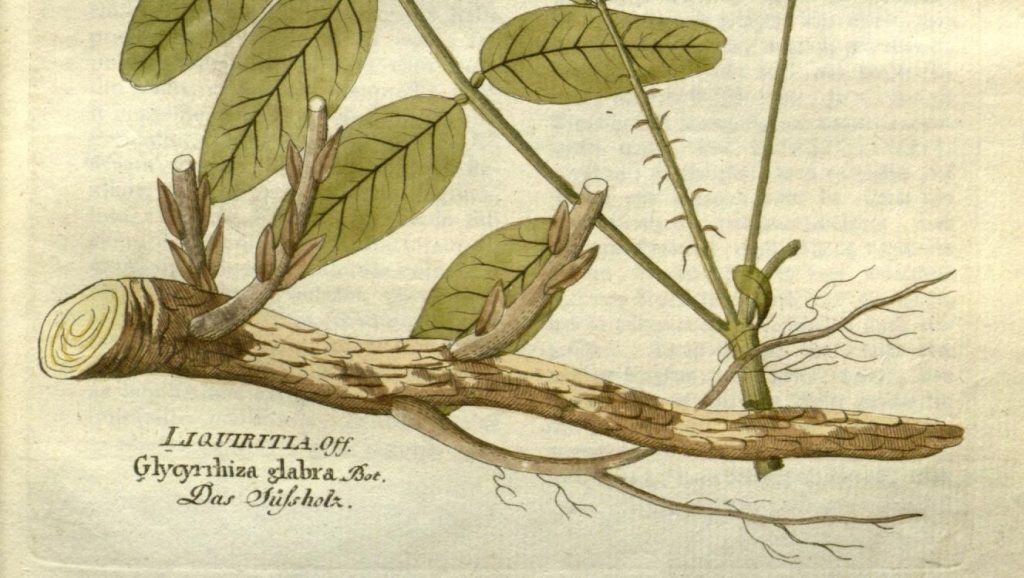

Example: Liquorice Root (Glycyrrhiza glabra)

Low dose (1-2 g/day dried root):

- Glycyrrhizin inhibits 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2

- Mild mineralocorticoid effect (beneficial for adrenal support)

Moderate dose (5-10 g/day):

- Therapeutic for gastric ulcers, anti-inflammatory effects

High dose (>15 g/day or prolonged use):

- Pseudoaldosteronism: Sodium retention, potassium loss, hypertension, edema

- Hypokalemic myopathy (muscle weakness)

Mechanism: Glycyrrhizin’s structural similarity to cortisol allows it to bind mineralocorticoid receptors, causing sodium retention and potassium excretion when consumed excessively.

Pharmacokinetic Variability

Absorption:

Bioavailability (percentage of administered dose reaching systemic circulation) varies based on:

Formulation:

- Tinctures: 20-80% bioavailability (alcohol enhances absorption)

- Teas: 10-40% bioavailability (water-soluble compounds only)

- Capsules: 15-60% bioavailability (depends on capsule dissolution rate)

Individual Factors:

- Gastric pH: Alkaloids absorb better in alkaline environment

- Food presence: Fat-soluble compounds (carotenoids) require dietary fat for absorption

- Gut microbiome: Bacteria metabolise flavonoid glycosides to more bioavailable aglycones

- Age: Decreased gastric acid secretion in elderly reduces absorption of some compounds

- Disease states: Inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease reduce absorption

First-Pass Metabolism:

Hepatic metabolism before compounds reach systemic circulation.

Example: Curcumin

Undergoes extensive glucuronidation and sulfation in liver and intestinal wall. Only 1% of orally administered curcumin reaches plasma in free form (Anand et al., 2007).

Distribution:

Depends on compound lipophilicity (fat-solubility):

- Lipophilic compounds (volatile oils): Readily cross blood-brain barrier, concentrate in adipose tissue

- Hydrophilic compounds (many glycosides): Remain in extracellular fluid, limited CNS penetration

Volume of Distribution (Vd):

Theoretical volume into which a drug distributes.

- High Vd: Extensive tissue distribution

- Low Vd: Remains primarily in plasma

Metabolism:

Phase I (oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis) and Phase II (conjugation) reactions, primarily hepatic.

Cytochrome P450 Enzymes:

Major metabolic enzymes with significant genetic polymorphism.

CYP2D6:

- ~7% of Caucasians are poor metabolizers (inactive enzyme variants)

- ~2-5% are ultra-rapid metabolizers (gene duplication)

- Affects metabolism of many alkaloids

Clinical Implication: Same dose may produce subtherapeutic levels in ultra-rapid metabolisers, toxic levels in poor metabolisers.

Elimination:

Renal Excretion:

- Hydrophilic compounds and Phase II conjugates excreted in urine

- Half-life typically 4-12 hours for most herbal compounds

Biliary Excretion:

- Larger molecules (>500 Da) and conjugates excreted in bile

- Undergoes enterohepatic recirculation (reabsorbed from intestine, prolonging effect)

Dosing Calculation Methodologies

Clark’s Rule (Weight-Based Pediatric Dosing):

Child dose = (Child’s weight in kg ÷ 70 kg) × Adult dose

Example:

Adult dose of chamomile tea: 200 ml

20 kg child dose: (20 ÷ 70) × 200 = 57 ml

Fried’s Rule (Age-Based for Infants):

Infant dose = (Age in months ÷ 150 months) × Adult dose

Young’s Rule (Age-Based for Children):

Child dose = [Age in years ÷ (Age + 12)] × Adult dose

Example:

Adult dose: 3 ml tincture

6-year-old child dose: [6 ÷ (6 + 12)] × 3 = [6 ÷ 18] × 3 = 1 ml

Limitations of Pediatric Dosing Rules:

- Based on body weight/age relationships, not pharmacokinetics

- Don’t account for organ maturity

- Broad estimates only

Safer Approach for Children:

- Use herbs specifically researched in pediatric populations

- Consult pediatric herbalist or healthcare provider

- Start with lowest calculated dose

- Prefer gentler herbs

Therapeutic Index Considerations

Therapeutic Index (TI) = (TI) = TD₅₀ / ED₅₀

Where:

- TD₅₀ = Dose producing toxicity in 50% of population

- ED₅₀ = Dose producing therapeutic effect in 50% of population

Wide therapeutic index (TI > 10):

Large safety margin (e.g., chamomile, peppermint, dandelion)

- Forgiving of dosing errors

- Suitable for self-administration

Narrow therapeutic index (TI < 3):

Small safety margin (e.g., cardiac glycoside-containing herbs like foxglove)

- Requires precise dosing

- Should only be administered by trained practitioners

- Not suitable for home use

Cumulative vs. Acute Dosing Strategies

Acute Dosing (Immediate Symptom Relief):

Higher doses at shorter intervals for rapid effect.

Example: Ginger for Nausea

- Dose: 2-4 g powdered ginger or 3-5 ml tincture

- Frequency: Every 2-4 hours as needed

- Duration: 1-3 days (acute episode)

Mechanism: Rapid serotonin (5-HT₃) receptor antagonism and prokinetic effects on gastric motility.

Chronic Dosing (Long-Term Support):

Moderate doses at regular intervals for cumulative effect.

Example: Hawthorn for Heart Failure

- Dose: 2-3 ml tincture or 300-600 mg extract

- Frequency: 2-3 times daily

- Duration: Minimum 4-8 weeks for effects; often long-term use

Mechanism: Gradual improvement in cardiac contractility, vasodilation, and antioxidant effects accumulate over weeks.

Overdosing Risks

Hepatotoxicity:

Comfrey (Symphytum officinale) Internal Use:

Contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs): symphytine, echimidine.

Mechanism of Hepatotoxicity:

- PAs undergo hepatic metabolism to pyrrole metabolites

- Pyrroles alkylate DNA and proteins, causing hepatocyte death

- Chronic use → hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD) → cirrhosis

Safe Practice: Comfrey for external use only (salves, poultices). Internal use banned in many countries.

Nephrotoxicity:

Aristolochic Acid Nephropathy:

Aristolochic acids (in Aristolochia species) cause progressive renal failure and urothelial cancer.

Substitution Error: Stephania tetrandra (Fang Ji, used for weight loss in TCM) adulterated with Aristolochia fangchi led to epidemic of renal failure in Belgium in 1990s.

Neurotoxicity:

Excessive Sage (Salvia officinalis) Use:

Thujone (monoterpene ketone in sage essential oil) is neurotoxic at high doses.

Mechanism: GABA-A receptor antagonism → seizures

Safe Dose: Culinary use safe; avoid high-dose essential oil internally or prolonged medicinal use (>2 weeks continuously).

6. Safety, Toxicology, and Contraindications

The “Natural = Safe” Fallacy

Cognitive Bias: Appeal to nature fallacy assumes anything natural is inherently safe.

Reality: Many of Earth’s most potent toxins are entirely natural:

- Botulinum toxin (Clostridium botulinum): LD₅₀ = 1-3 ng/kg (most toxic substance known)

- Ricin (from Ricinus communis castor beans): LD₅₀ = 1-20 mg/kg (inhibits ribosomal protein synthesis)

- Amatoxins (from Amanita phalloides mushrooms): LD₅₀ = 0.1 mg/kg (inhibits RNA polymerase II)

Herb-Drug Interactions: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Mechanisms

Pharmacokinetic Interactions (Affecting Drug Levels):

CYP450 Enzyme Induction:

St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum):

Hyperforin activates pregnane X receptor (PXR), inducing transcription of:

- CYP3A4 (metabolises ~50% of drugs)

- CYP2C9

- CYP2C19

- P-glycoprotein (drug efflux transporter)

Clinical Consequences:

- Reduces plasma levels of substrates by 20-90%

- Affects: Oral contraceptives (pregnancy risk), warfarin (thrombosis risk), cyclosporine (transplant rejection risk), HIV protease inhibitors (treatment failure), chemotherapy agents (reduced efficacy)

Mechanism Timeline:

- Induction begins: 3-7 days after starting St. John’s wort

- Maximal effect: 10-14 days

- Enzyme levels return to baseline: 1-2 weeks after stopping

CYP450 Enzyme Inhibition:

Grapefruit Juice (Not Technically Herbal but Important):

Furanocoumarins (bergamottin, 6′,7′-dihydroxybergamottin) irreversibly inhibit CYP3A4 in intestinal wall.

Clinical Consequences:

- Increases drug bioavailability 2-20 fold

- Affects: Statins (rhabdomyolysis risk), calcium channel blockers (severe hypotension), immunosuppressants (toxicity)

P-Glycoprotein Modulation:

Black Pepper (Piper nigrum) – Piperine:

Inhibits P-gp intestinal efflux pump, increasing absorption of:

- Curcumin (desired effect in supplements)

- Many drugs (potentially problematic)

Pharmacodynamic Interactions (Additive/Opposing Effects):

Anticoagulant/Antiplatelet Effects:

Herbs with Anticoagulant Properties:

- Garlic (Allium sativum): Allicin inhibits platelet aggregation

- Ginger (Zingiber officinale): Gingerols inhibit thromboxane synthesis

- Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba): Ginkgolides are PAF (platelet-activating factor) antagonists

- Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium): Parthenolide inhibits platelet aggregation

Risk When Combined with Warfarin, Aspirin, Clopidogrel:

- Additive anticoagulation

- Increased bleeding risk (ecchymoses, GI bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage in severe cases)

Evidence Level: Case reports exist, but controlled studies show modest effects. Clinical significance debated but caution warranted.

Hypoglycemic Effects:

Herbs Affecting Blood Glucose:

- Cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.): Improves insulin sensitivity

- Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum): Delays gastric emptying, enhances insulin secretion

- Gymnema (Gymnema sylvestre): Blocks sugar absorption, enhances insulin secretion

Risk When Combined with Diabetes Medications:

- Additive hypoglycemia

- Symptoms: Confusion, tremor, sweating, loss of consciousness

- Particularly dangerous with sulfonylureas, insulin

Monitoring Required: Blood glucose monitoring if combining herbs with diabetes medications.

Contraindications: Systematic Approach

Absolute Contraindications:

Situations where herb use is categorically unsafe.

Example: Kava (Piper methysticum) in Liver Disease

Kavalactones can cause idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity (mechanism unclear, possibly CYP2D6-related).

Documented cases: Acute liver failure requiring transplantation.

Contraindicated in: Any hepatic impairment, concurrent hepatotoxic medications, alcohol use disorder.

Relative Contraindications:

Situations requiring caution, monitoring, or dose adjustment.

Example: Liquorice in Hypertension

Glycyrrhizin’s mineralocorticoid effects can exacerbate hypertension.

Risk Management:

- Avoid if uncontrolled hypertension

- Monitor blood pressure if used

- Limit dose and duration

- Consider deglycyrrhisinated liquorice (DGL) as alternative

Pregnancy and Lactation Safety Categories

Adapting FDA Pregnancy Categories for Herbs:

Category A (Safe with evidence):

- Ginger (for nausea, first trimester): RCTs show safety

- Red raspberry leaf (third trimester): Traditional use, some supportive evidence

Category B (Probably safe, limited data):

- Peppermint (after first trimester)

- Chamomile (occasional use, normal tea amounts)

Category C (Unknown risk, avoid unless benefit outweighs risk):

- Most herbs fall here due to lack of pregnancy studies

- Lemon balm, nettle (insufficient data)

Category D (Evidence of risk):

- Sage (thujone, emmenagogue)

- Fennel (phytoestrogen, high doses)

- Fenugreek (uterine stimulant, high doses)

Category X (Contraindicated):

- Pennyroyal (pulegone causes abortion, maternal death)

- Rue (Ruta graveolens): Abortifacient

- Black cohosh: Potential hormonal effects

Lactation Considerations:

- Most herbs transfer to breastmilk in minimal amounts

- Avoid herbs contraindicated in infants (peppermint essential oil near infant’s face)

- Watch for infant reactions (digestive upset, drowsiness from sedative herbs)

Allergic Reactions and Cross-Reactivity

Type I Hypersensitivity (IgE-Mediated):

Immediate allergic reaction (within minutes to hours).

Symptoms: Urticaria, angioedema, bronchospasm, anaphylaxis

Plant Family Cross-Reactivity:

Asteraceae (Compositae) Family:

Includes: Chamomile, calendula, arnica, dandelion, echinacea, yarrow

Cross-reactive with: Ragweed, chrysanthemums, daisies

Allergenic Compounds: Sesquiterpene lactones

Clinical Recommendation: Patch test before widespread topical use if ragweed allergy present.

Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) Family:

Includes: Fennel, parsley, angelica, Queen Anne’s lace

Cross-reactive with: Celery, carrots, mugwort

Note: This family includes deadly hemlock — never forage without absolute certainty.

Patch Testing Protocol:

- Apply small amount of herb preparation to inner forearm

- Cover with bandage

- Leave for 24-48 hours

- Observe for erythema, pruritus, vesicles

- If reaction occurs, do not use herb internally or more widely

7. Quality Control and Contamination

Adulteration and Substitution

Economic Adulteration:

Addition of cheaper material to reduce production costs while maintaining appearance.

Example: Saffron Adulteration

True saffron (Crocus sativus): $10,000-20,000 NZD/kg

Common adulterants:

- Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) petals (similar colour)

- Turmeric-dyed plant material

- Synthetic dyes

Detection: Microscopy reveals cellular structures; chemical fingerprinting via HPLC.

Species Substitution:

Example: Echinacea Species Confusion

- Echinacea purpurea: Above-ground parts, high in chicoric acid

- Echinacea angustifolia: Root, high in alkamides

- Echinacea pallida: High in echinacoside

Problem: Studies show commercial products often mislabeled or contain wrong species (Gilroy et al., 2003).

Impact: Different species have different chemistry and clinical effects. Using wrong species may result in ineffective treatment.

Heavy Metal Contamination

Sources:

- Soil contamination (industrial pollution, mining, agricultural chemicals)

- Water used for irrigation

- Processing equipment

Toxic Metals of Concern:

- Lead (Pb): Neurotoxic, particularly dangerous in children

- Cadmium (Cd): Nephrotoxic, carcinogenic

- Mercury (Hg): Neurotoxic, bioaccumulates

- Arsenic (As): Carcinogenic, acute toxicity at high doses

Regulatory Limits (WHO/FDA Guidelines):

- Lead: <10 ppm in botanicals

- Cadmium: <0.3 ppm

- Mercury: <0.2 ppm

- Arsenic: <3 ppm

High-Risk Herbs:

Herbs grown in contaminated regions or those that bioaccumulate metals:

- Traditional Chinese herbs from certain regions (historical industrial contamination)

- Ayurvedic preparations (some traditional preparations intentionally include metals)

Prevention:

- Buy from reputable suppliers who test for heavy metals

- Look for third-party testing certificates (Certificate of Analysis/COA)

- Avoid herbs from unknown sources

- Grow your own in clean soil (test soil if concerned about contamination)

Pesticide Residues

Types:

- Organophosphates (chlorpyrifos, malathion)

- Carbamates (carbaryl)

- Pyrethroids (permethrin)

- Neonicotinoids (imidacloprid)

Health Concerns:

- Acute toxicity (rarely from herb consumption, but possible)

- Chronic low-level exposure (endocrine disruption, neurotoxicity)

- Organophosphates inhibit acetylcholinesterase (neurotoxic)

Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs):

Vary by compound and intended use. Many countries have limits for food crops but not always for medicinal herbs.

Prevention:

- Choose certified organic herbs

- Wash herbs thoroughly (removes surface residues)

- Know your supplier’s growing practices

- Grow your own without synthetic pesticides

Microbial Contamination

Bacteria:

- Salmonella spp.: Causes gastroenteritis

- Escherichia coli: Some strains pathogenic

- Staphylococcus aureus: Produces enterotoxins

Molds:

- Aspergillus spp.: Produces aflatoxins (carcinogenic)

- Penicillium spp.: Produces various mycotoxins

Acceptable Limits (Ph. Eur. Standards):

- Total aerobic microbial count: <10ā CFU/g for internal use herbs

- Yeast and mold: <10⁴ CFU/g

- E. coli: <10 CFU/g

- Salmonella: Absent in 25g sample

Control Measures:

- Proper drying (<12% moisture)

- Clean storage conditions

- Some suppliers use gamma irradiation or steam sterilisation (controversial — may degrade some compounds)

Authenticity Verification Methods

Macroscopic and Microscopic Examination:

- Visual inspection of whole herb (size, colour, morphology)

- Microscopic examination of cellular structures (trichomes, crystals, specialised cells)

- Requires botanical training and reference materials

Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC):

- Separates compounds on silica gel plate

- Creates characteristic “fingerprint” pattern

- Compare sample to authenticated reference standard

- Low-cost, accessible method

High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC):

- Separates and quantifies individual compounds

- “Gold standard” for quantification of marker compounds

- Example: Measure hypericin content in St. John’s wort to verify potency

- Expensive equipment, requires expertise

DNA Barcoding:

- Amplifies and sequences specific DNA regions (ITS, matK, rbcL)

- Compares to reference database (GenBank, BOLD)

- Definitive identification, works on powdered material

- Increasing accessibility (specialised labs offer service)

8. Methodological Selection Errors

Solvent-Compound Specificity

Polarity and “Like Dissolves Like” Principle:

Chemical compounds dissolve in solvents of similar polarity:

- Polar solvents (water, alcohol): Dissolve polar compounds

- Non-polar solvents (oils, fats): Dissolve non-polar compounds

Polarity Scale:

Water (most polar) > Methanol > Ethanol > Acetone > Chloroform > Hexane (non-polar)

Water Extraction (Teas, Infusions, Decoctions)

Compounds Extracted:

- Highly polar: Minerals (calcium, magnesium, iron salts)

- Polysaccharides: Mucilage, pectins, inulin

- Tannins: Polyphenols (hydrolysable and condensed tannins)

- Glycosides: Sugar-bound compounds (e.g., salicin, cardiac glycosides)

- Some flavonoids: Particularly flavonoid glycosides

- Water-soluble vitamins: Vitamin C, B-complex

Poorly Extracted:

- Alkaloids (many are weak bases, need alkaline extraction or alcohol)

- Volatile oils (evaporate during heating)

- Resins (too lipophilic)

Example Appropriate for Water:

Nettle leaf (Urtica dioica) for minerals

- High in calcium, magnesium, iron, silica

- These minerals dissolve well in water

- Long infusion (4-8 hours) maximises extraction

- Method: 30g dried nettle in 1 litre just-boiled water, steep covered 4-8 hours

Alcohol Extraction (Tinctures)

Ethanol is amphipathic: Has both polar (-OH group) and non-polar (ethyl chain) properties.

Compounds Extracted:

- Alkaloids: Particularly as salts (berberine, caffeine, morphine)

- Volatile oils: Terpenes, phenylpropanoids

- Flavonoid aglycones: Non-sugar-bound forms

- Glycosides: Yes, but water is often better for some

- Resins: High alcohol % needed (>60%)

- Some tannins: Less efficiently than water

Alcohol Percentage Matters:

95% Alcohol (High-proof):

- Best for: Resins, volatile oils, fresh plant material

- Example: Fresh St. John’s wort flowers (high water content requires starting with 95% to achieve ~70% final)

60-70% Alcohol:

- Best for: Most dried herbs with volatile oils, roots with alkaloids/resins

- Example: Valerian root, echinacea root, aromatic herbs

40-50% Alcohol (Vodka):

- Best for: Most dried leaves and flowers, general-purpose

- Example: Chamomile, nettle leaf, hawthorn

25-40% Alcohol:

- Best for: Glycoside-rich herbs

- Less common, often add water to higher-proof alcohol

Example Appropriate for Alcohol:

Echinacea root (Echinacea angustifolia) for alkamides

- Alkamides are lipophilic (not water-soluble)

- Require 60-70% alcohol for extraction

- Method: 1:5 dried root in 60% alcohol, macerate 4-6 weeks

Oil Extraction (Infused Oils)

Compounds Extracted:

- Lipophilic volatile oils: Monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes

- Carotenoids: β-carotene, lutein, lycopene

- Fat-soluble vitamins: Vitamin E, some vitamin K

- Resins: Partially

- Chlorophyll: Partially (gives green colour)

Not Extracted:

- Minerals

- Water-soluble vitamins

- Glycosides

- Tannins

- Alkaloids (mostly)

Example Appropriate for Oil:

Calendula flowers for carotenoids

- Carotenoids (lutein, β-carotene) are fat-soluble

- Responsible for skin-healing and anti-inflammatory effects

- Method: Solar or heat infusion in olive oil, 4-6 weeks

Vinegar Extraction

Acetic Acid Properties:

- Weak acid (pKa 4.76)

- Protonates weak bases (extracts some alkaloids)

- Excellent mineral solvent

Compounds Extracted:

- Minerals: Extremely effective (forms soluble acetate salts)

- Some alkaloids: As acetate salts

- Some flavonoids

- Acetic acid acts as preservative: Antibacterial properties

Example Appropriate for Vinegar:

Dandelion root for minerals and bitters

- Minerals (potassium, calcium) extract as acetate salts

- Sesquiterpene lactones (bitters) partially extract

- Method: 1:4 dried root in apple cider vinegar, macerate 4-6 weeks

Common Mismatch Errors

Error: Water Tea of Resinous Herb

Example: Calendula flower tea for topical use

Problem:

- Carotenoids and resins poorly soluble in water

- Resulting tea is weak, ineffective for topical anti-inflammatory use

Solution: Make infused oil instead (extracts lipophilic anti-inflammatory compounds).

Error: Alcohol Tincture of Mineral-Rich Herb

Example: Nettle leaf tincture for iron supplementation

Problem:

- Iron salts poorly soluble in alcohol

- Mineral content of tincture is minimal

Solution: Make long water infusion instead (4-8 hours extracts minerals efficiently).

Error: Oil Infusion for Water-Soluble Compounds

Example: Infused oil of rose hips for vitamin C

Problem:

- Vitamin C is water-soluble, not fat-soluble

- Essentially none extracts into oil

Solution: Make syrup or tea instead.

9. Expectation and Timeline Mismanagement

Pharmaceutical vs. Herbal Therapeutic Models

Pharmaceutical “Magic Bullet” Model:

- Single compound

- High potency

- Rapid, dramatic effect

- Symptom suppression

- Often side effects

Example: Ibuprofen for headache

- Mechanism: COX-1 and COX-2 inhibition

- Effect: Blocks prostaglandin synthesis

- Onset: 30-60 minutes

- Result: Pain relief (symptomatic)

Herbal “Holistic Support” Model:

- Multiple compounds

- Moderate potency

- Gradual, gentle effect

- Body system support

- Usually minimal side effects

Example: Feverfew for migraine prevention

- Mechanism: Parthenolide inhibits platelet aggregation, serotonin release, inflammatory mediators

- Effect: Reduces migraine frequency and severity

- Onset: 2-6 weeks of consistent use

- Result: Prevention (addresses underlying patterns)

Realistic Therapeutic Timelines

Acute Conditions (Rapid Response):

Digestive Upset:

- Ginger for nausea: 15-30 minutes

- Peppermint for gas/bloating: 20-40 minutes

- Mechanism: Direct smooth muscle relaxation, gastric motility effects

Anxiety (Mild):

- Chamomile tea: 30-60 minutes

- Lemon balm tea: 30-60 minutes

- Mechanism: GABA modulation, onset similar to benzodiazepines but much milder

Topical Applications:

- Plantain poultice for insect sting: 5-15 minutes (symptomatic relief)

- Calendula salve for minor wound: Days for healing (not immediate)

Sub-Acute Conditions (Days to Weeks):

Sleep Support:

- Valerian: 7-14 days for consistent effect

- Mechanism: GABAergic effects cumulative, sleep architecture improves over time

Immune Support:

- Echinacea: 7-10 days to reduce cold duration (start at first symptoms)

- Elderberry syrup: 2-4 days to reduce flu symptoms

Chronic Conditions (Weeks to Months):

Adaptogenic Stress Support:

- Ashwagandha, holy basil: 4-8 weeks

- Mechanism: HPA axis modulation, cortisol regulation takes time

Cardiovascular Support:

- Hawthorn for heart failure: 6-12 weeks minimum

- Mechanism: Cumulative improvements in contractility, vasodilation

Mood Support:

- St. John’s wort for depression: 4-6 weeks (similar timeline to SSRIs)

- Mechanism: Neurotransmitter modulation takes time

10. Documentation and Standardisation

The Critical Importance of Labeling

Legal Requirements (Commercial):

In most jurisdictions, commercial herbal products must display:

- Product name

- Ingredients (all herbs, other components)

- Quantity/volume

- Batch number

- Expiration date

- Manufacturer information

- Directions for use

- Safety warnings

Home Herbalist Best Practices:

While not legally required for personal use, proper labeling is essential for:

- Safety: Avoiding accidental misuse

- Efficacy: Knowing when product is no longer potent

- Learning: Tracking what works and what doesn’t

Essential Label Information:

For Dried Herbs:

Herb: Calendula (Calendula officinalis)

Part: Flowers

Source: Grown in garden, Auckland

Harvest Date: 15 Jan 2024

Storage: Opened 1 Feb 2024

For Tinctures:

Herb: Valerian Root (Valeriana officinalis)

Ratio: 1:5

Alcohol: 70% ethanol

Preparation Date: 1 March 2024

Strain Date: 15 April 2024

Dose: 2-4ml before bed

For Infused Oils:

Herbs: Calendula flowers + St John's wort flowers

Oil: Olive oil

Method: Solar infusion

Date Made: 1 Dec 2023

Vitamin E Added: Yes (0.1%)

Use: External only

Batch Records and Reproducibility

Professional Standard (Adaptable for Home Use):

Batch Record Template:

Batch Number: VAL-2024-001

Product: Valerian Root Tincture

Date: 1 March 2024

INGREDIENTS:

- Valerian root (Valeriana officinalis), dried: 100g

Source: Organic supplier, Lot #12345

- Alcohol: 500ml at 70% (350ml 95% vodka + 150ml water)

METHOD:

- Root chopped to 2-3mm pieces

- Placed in 1L glass jar

- Covered with alcohol mixture

- Stored in dark cupboard at ~20°C

- Shook daily for first week, then 3x/week

- Maceration time: 6 weeks

PROCESSING:

- Strained through muslin 15 April 2024

- Pressed marc thoroughly

- Final volume: 480ml

- colour: Dark amber-brown

- Odor: Strong, characteristic valerian

- Bottled in 50ml amber dropper bottles (10 bottles)

QUALITY OBSERVATIONS:

- No mold, contamination, or off-odors

- Good colour extraction

- Strong characteristic aroma

LABELING:

- Valerian Root Tincture 1:5 @ 70%

- Dose: 2-4ml before bed

- Made: 1 Mar 2024

- Best Before: 1 Mar 2029

Why This Matters:

- Reproducibility: Can remake exactly if batch is effective

- Troubleshooting: Can identify what went wrong if batch fails

- Learning: Builds knowledge base over time

- Safety: Clear record of ingredients in case of reaction

Standardisation vs. Whole Plant Variability

Pharmaceutical Standardisation:

Extracts standardised to contain specific percentage of marker compound.

Example: St. John’s Wort Standardised Extract

- Standardised to 0.3% hypericin and 3-5% hyperforin

- Ensures consistent dosing

- Research uses standardised extracts

Challenges:

- Expensive, requires analytical equipment (HPLC)

- Focuses on single compound (may not capture full activity)

- Natural variation in plants makes standardisation difficult

Whole Plant Approach (Home Herbalism):

Uses entire herb, accepting natural variation.

Advantages:

- Preserves synergy of multiple compounds

- More accessible (no analytical equipment needed)

- Traditional approach with long history

Disadvantages:

- Batch-to-batch variation

- Harder to dose precisely

- Less suitable for narrow therapeutic window herbs

Compromise Approach:

Use consistent preparation methods (same ratio, alcohol %, time) to minimise variation, accept some natural variability.

Conclusion: Transitioning from Novice to Competent Practitioner

Becoming a skilled herbalist requires:

- Replacing intuitive guesswork with systematic, knowledge-based practice

- Understanding underlying scientific and ethical principles

- Building safety infrastructure (proper ID, checking contraindications, monitoring)

- Accepting the learning process (mistakes will happen, learn from them)

- Committing to continuing education (herbal science evolves)

The Path Forward:

Beginner Phase (Months 1-6):

- Master 3-5 herbs completely

- Focus on safety (ID, contraindications, drug interactions)

- Use simple preparations (single herb teas, basic tinctures)

- Keep detailed notes

Intermediate Phase (Months 6-24):

- Expand to 10-15 herbs

- Begin simple formulations (2-3 herb combinations)

- Understand preparation method selection

- Study plant families and phytochemistry basics

Advanced Phase (Years 2+):

- Deep knowledge of 20-30+ herbs

- Complex formulation based on traditional patterns

- Understanding pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

- Potentially formal training (herbalist certification programs)

Professional Practice (Optional):

- Formal education (degree programs in herbal medicine)

- Clinical training

- Understanding of scope of practice and referral

- Continuing education and professional development

Sources & Further Reading

Botanical Identification & Toxicology

Froberg, B., Ibrahim, D., & Furbee, R. B. (2007). Plant poisoning. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 25(2), 375-409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2007.02.013

Vetter, J. (2004). Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum L.). Food and Chemical Toxicology, 42(9), 1373-1382.

Pharmacokinetics & Herb-Drug Interactions

Zhou, S., Chan, E., Pan, S. Q., Huang, M., & Lee, E. J. (2004). Pharmacokinetic interactions of drugs with St John’s wort. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 18(2), 262-276.

Shoba, G., Joy, D., Joseph, T., Majeed, M., Rajendran, R., & Srinivas, P. S. (1998). Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers. Planta Medica, 64(4), 353-356.

Quality Control & Adulteration

Gilroy, C. M., Steiner, J. F., Byers, T., Shapiro, H., & Georgian, W. (2003). Echinacea and truth in labeling. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(6), 699-704.

Safety & Contraindications

Ekor, M. (2014). The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 4, 177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2013.00177

Comprehensive Texts

Bone, K., & Mills, S. (2013). Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone.

Gardner, Z., & McGuffin, M. (2013). American Herbal Products Association’s Botanical Safety Handbook (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

Hoffmann, D. (2003). Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press.

Mills, S., & Bone, K. (2005). The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety. Churchill Livingstone.

New Zealand Resources

New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. (n.d.). Plant Lists & Resources. Retrieved from https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/

National Poisons Centre. (2023). Poisons Information. University of Otago. Retrieved from https://www.poisons.co.nz/

Disclaimer: This guide is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice or replace proper medical diagnosis and treatment. The information provided is based on current scientific understanding and traditional knowledge but should not be used as a substitute for consultation with qualified healthcare practitioners. Plant identification, preparation, and use carry inherent risks. Readers are solely responsible for their own safety, for correctly identifying plant materials, for understanding contraindications and interactions with their specific health conditions and medications, and for complying with all applicable laws and regulations. When in doubt, always consult qualified professionals including botanists for identification verification, medical herbalists for preparation guidance, and licensed healthcare providers for health conditions. The author and publisher assume no liability for any adverse effects, injuries, or legal consequences resulting from the use of information contained in this guide.

Note on Pricing: All prices mentioned in this guide are approximate and based on New Zealand suppliers as of December 2025. Prices vary by supplier, season, and market conditions. We recommend checking current prices with your local suppliers.