Pain Physiology, Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms, and Analgesic Pathways

Cultural Context: This guide addresses pain from a Western scientific perspective. Rongoā Māori has its own frameworks for pain management—consult Te Paepae Motuhake for traditional knowledge.

Scope: Western pain physiology, pharmacology, phytochemical analgesic/anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

The Pharmacology and Mechanisms of Natural Pain Relief

This comprehensive guide explores the biochemical mechanisms underlying pain and inflammation, and how specific herbal compounds interact with these pathways to provide relief. We’ll examine the inflammatory cascade, pain signaling pathways, and the detailed pharmacology of key pain-relieving herbs.

Table of Contents

- The Inflammatory Cascade and Pain Physiology

- Ginger: Dual COX-LOX Inhibition

- Turmeric: Multi-Target Anti-Inflammatory

- Willow Bark: Salicylate Pharmacology

- Capsaicin: Neuropeptide Depletion and TRPV1

- Topical vs Systemic Approaches

- Clinical Applications and Formulation

- References

The Inflammatory Cascade and Pain Physiology

Arachidonic Acid Metabolism

When tissue is injured, cell membranes are disrupted, releasing arachidonic acid (AA)—a 20-carbon polyunsaturated fatty acid stored in membrane phospholipids. AA then enters one of two major enzymatic pathways:

1. Cyclooxygenase (COX) Pathway:

COX-1 (Constitutive):

- Present continuously in most tissues

- Functions:

- Gastric mucosa protection (stimulates mucus and bicarbonate secretion)

- Platelet aggregation (via thromboxane A2)

- Renal blood flow regulation

- Homeostatic prostaglandin production

COX-2 (Inducible):

- Normally low or absent

- Rapidly induced by:

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α)

- Growth factors

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

- Stress

- Tissue injury

COX-2 mRNA characteristics:

- Contains 3′-untranslated instability sequences (AUU-rich elements)

- Rapid turnover (half-life ~30 minutes)

- Allows quick upregulation/downregulation

COX Products:

Arachidonic Acid

→ COX-1 or COX-2

Prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) [unstable intermediate]

→ Tissue-specific synthases

├→ PGE2 (pain, fever, inflammation)

├→ PGI2/Prostacyclin (vasodilation, inhibits platelet aggregation)

├→ PGD2 (sleep, vasodilation)

├→ PGF2α (uterine contraction)

└→ Thromboxane A2 (TXA2) (platelet aggregation, vasoconstriction)

PGE2 (Prostaglandin E2)—The Primary Pain Mediator:

Mechanism of pain sensitisation:

- PGE2 binds to EP receptors (EP1, EP2, EP3, EP4) on nociceptors

- Activates protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC)

- Phosphorylates ion channels:

- TRPV1 (heat/capsaicin receptor)—lowers activation threshold

- Sodium channels (Nav1.7, Nav1.8, Nav1.9)—increases excitability

- Result: Neurons fire more easily = hyperalgesia (increased pain from painful stimuli) and allodynia (pain from normally non-painful stimuli)

Additional PGE2 effects:

- Increases vascular permeability (edema/swelling)

- Fever induction (acts on hypothalamic thermoregulatory center)

- Vasodilation (redness, heat)

2. Lipoxygenase (LOX) Pathway:

Multiple LOX enzymes exist; 5-LOX is most important for inflammation:

Arachidonic Acid

→ 5-LOX

5-HPETE (5-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid)

→

Leukotriene A4 (LTA4)

→

├→ LTB4 (potent neutrophil chemoattractant)

└→ LTC4, LTD4, LTE4 (bronchoconstriction, vascular permeability)

LTB4 Functions:

- Neutrophil chemotaxis (attracts white blood cells to injury)

- Increases vascular permeability

- Promotes leukocyte adhesion to endothelium

- Amplifies inflammatory response

Why LOX pathway matters:

- COX inhibitors (NSAIDs) don’t affect LOX pathway

- LOX products continue driving inflammation

- Some conditions (asthma, inflammatory bowel disease) heavily LOX-mediated

- Dual COX-LOX inhibitors (like ginger) provide broader anti-inflammatory effect

NF-κB: The Master Inflammation Switch

Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-κB):

Structure:

- Transcription factor (protein complex that binds DNA)

- Heterodimer: Usually p65 (RelA) + p50 subunits

- Normally sequestered in cytoplasm by IκB (inhibitor of κB)

Activation pathway:

- Stimulus: Cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β), LPS, oxidative stress, injury

- IKK activation: IκB kinase (IKK) complex activated

- IκB phosphorylation: IKK phosphorylates IκB at serine residues

- IκB degradation: Phosphorylated IκB ubiquitinated and degraded by proteasome

- NF-κB released: Free to translocate to nucleus

- Gene transcription: Binds to κB sites in DNA, activates gene transcription

NF-κB target genes (>500 genes):

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8

- Adhesion molecules: ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin

- Chemokines: MCP-1, MIP-1α

- Enzymes: COX-2, iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase)

- Acute phase proteins: C-reactive protein (CRP)

Why NF-κB is critical:

- Amplifies inflammation (produces cytokines that activate more NF-κB)

- Positive feedback loop

- Blocking NF-κB = turning off inflammation at the source

- Many anti-inflammatory herbs target NF-κB

Pain Signal Transmission

Nociceptor Types:

Aδ fibers (myelinated):

- Fast pain (0.5-30 m/s conduction)

- Sharp, localised, immediate

- “First pain”—touching hot stove

C fibers (unmyelinated):

- Slow pain (0.5-2 m/s conduction)

- Dull, aching, diffuse

- “Second pain”—throbbing after injury

- More abundant than Aδ

- Primary target of capsaicin

Neurotransmitters in pain:

Substance P (SP):

- 11-amino acid neuropeptide

- Released from C-fiber terminals (peripheral and central)

- Binds NK1 receptors (neurokinin 1)

- Functions:

- Pain signal transmission (spinal cord dorsal horn)

- Neurogenic inflammation (periphery)

- Smooth muscle contraction

- Vasodilation

Glutamate:

- Main excitatory neurotransmitter

- Released with Substance P

- Binds AMPA, NMDA, kainate receptors

- Essential for pain transmission

CGRP (Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide):

- Co-released with Substance P

- Potent vasodilator

- Involved in migraine pathophysiology

- Neurogenic inflammation

Peripheral vs Central Sensitisation:

Peripheral sensitisation:

- Nociceptors become more sensitive

- Lower activation threshold

- Caused by “inflammatory soup”: PGE2, bradykinin, serotonin, histamine

- Result: Primary hyperalgesia (increased pain at injury site)

Central sensitisation:

- Spinal cord dorsal horn neurons become hyperexcitable

- Increased synaptic strength

- Expanded receptive fields

- Result: Secondary hyperalgesia (pain in areas surrounding injury), allodynia

Ginger: Dual COX-LOX Inhibition

Phytochemistry

Gingerols (Fresh Ginger):

Structure: Phenolic compounds with alkyl side chain

Main gingerols:

- [6]-Gingerol: Most abundant (0.3-3% fresh weight)

- [8]-Gingerol: Less abundant but potent

- [10]-Gingerol: Minor constituent

Chemical formula (6-gingerol): C17H26O4

Shogaols (Dried/Heated Ginger):

Formation: Dehydration of gingerols during drying or cooking

- [6]-Gingerol → [6]-Shogaol (loses H2O)

Characteristics:

- More potent than gingerols

- More stable

- Higher in dried ginger, ginger powder

- Concentration increases with heat

Why shogaols are more potent:

- Better cell membrane penetration (more lipophilic)

- Stronger enzyme inhibition

- Enhanced anti-inflammatory activity

Other constituents:

- Paradols: Further degradation products

- Zingerone: Formed during cooking (sweet, spicy)

- Essential oils: Zingiberene, β-sesquiphellandrene (10-15% of oleoresin)

Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms

1. COX-2 Inhibition:

Mechanism:

- Gingerols and shogaols bind COX-2 active site

- Non-selective COX inhibition: Also inhibit COX-1 (but less than aspirin)

- Reduce PGE2, PGI2, TXA2 production

IC50 values (concentration for 50% inhibition):

- [6]-Shogaol: ~5 μM (COX-2)

- [6]-Gingerol: ~10-15 μM (COX-2)

- For comparison, ibuprofen IC50: ~5-10 μM

Clinical significance:

- Reduces prostaglandin-mediated pain, inflammation, fever

- Less gastric irritation than NSAIDs (weaker COX-1 inhibition)

2. 5-LOX Inhibition (Unique Advantage):

Mechanism:

- Gingerols inhibit 5-lipoxygenase

- Reduces LTB4 and cysteinyl leukotrienes

- Dual inhibition = broader anti-inflammatory effect

Why this matters:

- NSAIDs only block COX → may shunt AA to LOX pathway

- Can worsen asthma, inflammatory bowel disease

- Ginger blocks both → more complete inflammation control

IC50 for 5-LOX: ~15-20 μM (shogaols)

3. NF-κB Suppression:

Mechanism:

- Gingerols prevent IKK activation

- Blocks IκB phosphorylation and degradation

- NF-κB remains sequestered in cytoplasm

- Result: Downstream inflammatory gene transcription prevented

Effects:

- Reduced COX-2 expression (different from direct COX-2 inhibition)

- Reduced iNOS expression (less nitric oxide production)

- Reduced cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6)

4. Antioxidant Activity:

Mechanism:

- Phenolic structure scavenges free radicals

- Reduces oxidative stress in inflamed tissues

- Prevents lipid peroxidation

Significance:

- Oxidative stress activates NF-κB

- Antioxidants provide indirect anti-inflammatory effect

- Protects tissues during inflammation

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption:

- Gingerols absorbed in small intestine

- Bioavailability moderate (affected by food, formulation)

- Peak plasma levels: 30-60 minutes

Distribution:

- Widely distributed to tissues

- Cross blood-brain barrier (modest)

- Accumulate in GI tract

Metabolism:

- Phase I: Cytochrome P450 oxidation, reduction

- Phase II: Glucuronidation, sulfation

- Major metabolites retain some activity

Excretion:

- Primarily urine (glucuronide conjugates)

- Bile (enterohepatic recirculation possible)

- Half-life: 1-3 hours (necessitates multiple daily doses)

Clinical Evidence

Muscle Soreness (DOMS):

Black et al. (2010) study:

- 74 participants, double-blind, placebo-controlled

- Eccentric arm exercises (muscle damage model)

- 2g ginger daily vs placebo, 11 days

- Results:

- 25% reduction in muscle pain 24 hours post-exercise

- Reduced inflammatory markers (PGE2 in muscle)

- Effect comparable to NSAIDs

Osteoarthritis:

Altman & Marcussen (2001):

- 247 patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Ginger extract vs placebo, 6 weeks

- Results:

- Significant pain reduction

- Improved function

- Effect size moderate (not as strong as NSAIDs but significant)

Mechanism in OA:

- Reduces cartilage inflammation

- Inhibits matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)—enzymes that degrade cartilage

- Antioxidant protection of chondrocytes

Turmeric: Multi-Target Anti-Inflammatory

Curcumin Phytochemistry

Structure:

- Diferuloylmethane

- Two ferulic acid molecules linked by methylene bridge

- Highly conjugated structure (gives yellow color)

Chemical formula: C21H20O6

Molecular weight: 368.38 Da

Physical properties:

- Lipophilic (fat-soluble)

- Poorly water-soluble

- pKa ~8.5 (mostly uncharged at physiological pH)

Curcuminoids in Turmeric:

- Curcumin: 70-80% of curcuminoid fraction

- Demethoxycurcumin: 15-20%

- Bisdemethoxycurcumin: 5-10%

Total curcuminoid content: 2-8% in dried rhizome (varies by cultivar, growing conditions)

Multi-Target Mechanisms

1. NF-κB Inhibition (Primary Mechanism):

Multiple points of interference:

a) IKK inhibition:

- Curcumin directly binds and inhibits IKK complex

- Prevents IκB phosphorylation

- NF-κB cannot translocate to nucleus

b) Direct NF-κB binding:

- Curcumin may bind p65 subunit directly

- Prevents DNA binding even if NF-κB reaches nucleus

c) Reduced NF-κB DNA binding:

- Alters p65 phosphorylation state

- Reduces transcriptional activity

Result: Comprehensive block of NF-κB pathway

2. COX-2 Inhibition:

Dual mechanism:

a) Direct enzyme inhibition:

- Curcumin binds COX-2 active site

- IC50: ~10-20 μM

- Reduces prostaglandin synthesis

b) Reduced COX-2 expression:

- Via NF-κB inhibition

- Less COX-2 mRNA transcription

- Long-term downregulation

3. LOX Inhibition:

5-LOX and 12-LOX inhibition:

- Reduces leukotriene synthesis

- IC50: ~5-10 μM (5-LOX)

- Broader anti-inflammatory effect than COX inhibition alone

4. Additional Molecular Targets:

a) MAPK pathways:

- Inhibits p38 MAPK, JNK, ERK

- These kinases activate transcription factors (including NF-κB)

- Reduces inflammatory gene expression

b) JAK-STAT pathway:

- Inhibits Janus kinases (JAK)

- Prevents STAT phosphorylation and nuclear translocation

- Reduces cytokine signaling

c) Antioxidant activity:

- Phenolic structure scavenges ROS (reactive oxygen species)

- Induces antioxidant enzymes (heme oxygenase-1, glutathione S-transferase)

- Protects against oxidative stress

The Bioavailability Challenge

Poor absorption:

- Only ~1% absorbed from GI tract

- Poor water solubility

- Rapid metabolism

First-pass metabolism:

- Extensive glucuronidation and sulfation in intestine and liver

- Most curcumin converted to metabolites before reaching systemic circulation

Curcumin metabolites:

- Curcumin glucuronide

- Curcumin sulfate

- Tetrahydrocurcumin

- Most metabolites have reduced activity

Strategies to enhance bioavailability:

1. Piperine (Black Pepper):

- Mechanism: Inhibits glucuronidation enzymes (UGT)

- Effect: 2000% increase in curcumin bioavailability

- Dose: 20mg piperine with 2g curcumin

- Why it works: Slows curcumin metabolism, allows more absorption

2. Lipid formulations:

- Curcumin in phospholipids (Meriva®)

- Nano-emulsions

- Improves absorption in lipophilic environment

3. Liposomal curcumin:

- Curcumin encapsulated in liposomes

- Protects from degradation

- Enhances cellular uptake

4. Curcumin-phytosome:

- Curcumin complexed with phosphatidylcholine

- Up to 29-fold increase in bioavailability

Clinical Evidence

Osteoarthritis:

Kuptniratsaikul et al. (2014):

- 367 patients with knee OA

- Curcuma domestica extract (1500mg curcuminoids) vs ibuprofen (1200mg)

- 4 weeks

- Results:

- Comparable pain reduction

- Similar improvement in function

- Fewer GI adverse events with curcumin

Rheumatoid Arthritis:

Chandran & Goel (2012):

- 45 patients with active RA

- Curcumin vs diclofenac vs combination

- 8 weeks

- Results:

- Curcumin alone: Significant improvement in DAS28 score (disease activity)

- Comparable to diclofenac

- Better safety profile

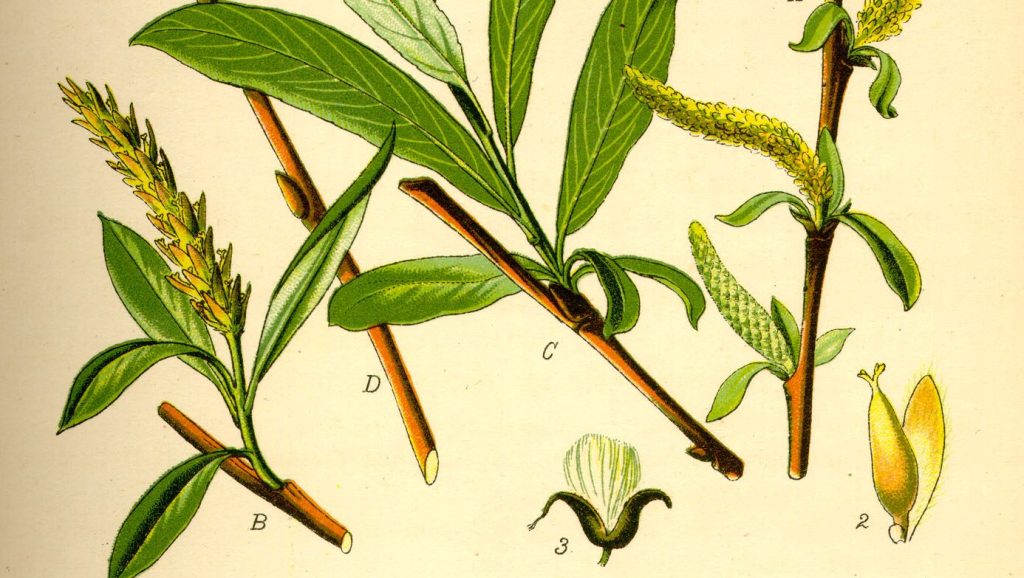

Willow Bark: Salicylate Pharmacology

Phytochemistry

Salicin:

- Phenolic glycoside

- Structure: Salicyl alcohol + glucose

- Molecular formula: C13H18O7

- Concentration in bark: 1-10% (varies by species)

Willow species and salicin content:

- Salix alba (White Willow): 1-3%

- Salix purpurea (Purple Willow): 3-7%

- Salix fragilis (Crack Willow): 2-5%

Other constituents:

- Salicortin, tremulacin: Related phenolic glycosides

- Flavonoids: Isoquercitrin, rutin (antioxidant, anti-inflammatory)

- Tannins: Astringent, anti-inflammatory

Metabolism and Mechanism

Prodrug activation:

Salicin (inactive)

→ Intestinal bacteria β-glucosidase

Saligenin (salicyl alcohol)

→ Hepatic oxidation

Salicylic acid (active)

Salicylic acid mechanisms:

1. COX inhibition:

- Non-selective: Inhibits both COX-1 and COX-2

- Mechanism: Acetylates serine residue in COX active site

- Irreversible (aspirin) vs reversible (salicylic acid from willow)

- Reduces prostaglandin synthesis

Difference from aspirin:

- Aspirin = acetylsalicylic acid (acetyl group)

- Willow salicylic acid lacks acetyl group

- May be gentler on stomach (less direct irritation, though debate exists)

2. Anti-inflammatory effects:

- Reduces PGE2, TXA2 synthesis

- Inhibits neutrophil activation

- Reduces inflammatory cytokines

3. Analgesic effects:

- Both peripheral (reduced prostaglandins) and central (spinal cord effects)

- Reduces pain signal transmission

4. Antipyretic:

- Reduces PGE2 in hypothalamus

- Lowers fever set-point

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption:

- Slow (salicin must be cleaved by gut bacteria)

- Time to peak effect: 2-4 hours (vs 30-60 min for aspirin)

- Advantage: Sustained release effect

Distribution:

- Salicylates widely distributed

- Cross blood-brain barrier

- Protein-bound (~50-80%)

Metabolism:

- Hepatic conjugation

- Forms salicyluric acid, gentisic acid

Excretion:

- Primarily renal

- pH-dependent (alkaline urine increases excretion)

- Half-life: 2-3 hours (dose-dependent)

Clinical Evidence

Low Back Pain:

Chrubasik et al. (2000):

- 210 patients with chronic low back pain

- Willow bark extract (standardised to 120mg or 240mg salicin) vs placebo

- 4 weeks

- Results:

- 240mg dose: 39% pain-free at 4 weeks (vs 6% placebo)

- Significant improvement in function

- Good tolerability

Osteoarthritis:

Schmid et al. (2001):

- 78 patients with OA

- Willow bark vs placebo

- 2 weeks

- Results:

- Reduced pain intensity

- Improved quality of life

- Fewer adverse events than NSAIDs

Safety Considerations

Contraindications:

- Aspirin allergy (cross-sensitivity)

- Peptic ulcer disease (may irritate stomach lining)

- Bleeding disorders (antiplatelet effects)

- Children with fever (Reye’s syndrome risk—theoretical with salicin)

- Pregnancy/lactation (salicylates cross placenta)

Drug interactions:

- Anticoagulants (warfarin): Increased bleeding risk

- NSAIDs: Additive effects, increased GI risk

- Methotrexate: Salicylates reduce renal clearance

Comparison to aspirin:

- Lower doses of salicylate from willow vs typical aspirin dose

- May be gentler (debated—still contains salicylates)

- Slower onset (prodrug activation)

- Longer duration (sustained release)

Capsaicin: Neuropeptide Depletion and TRPV1

TRPV1 Receptor Biology

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 (TRPV1):

Structure:

- Non-selective cation channel (Ca²⁺, Na⁺)

- Six transmembrane domains

- Tetramer (four subunits form functional channel)

- Located on C-fiber nociceptors

Physiological activators:

- Heat: >43°C (threshold for tissue damage)

- Acidic pH: <6.0 (tissue injury, inflammation)

- Endovanilloids: Anandamide, N-arachidonoyl-dopamine

TRPV1 location:

- Primary sensory neurons (dorsal root ganglia, trigeminal ganglia)

- Central terminals: Spinal cord dorsal horn

- Peripheral terminals: Skin, viscera, joints

Function in pain:

- Detects noxious heat and chemical irritants

- Opens in response to tissue damage signals

- Ca²⁺ influx → depolarisation → action potential → pain signal

Capsaicin Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action:

Phase 1: Activation (Seconds to Minutes)

- Capsaicin binds TRPV1:

- Binds intracellular side of channel

- Lowers activation threshold to ~37°C (body temperature)

- Channel opens even without heat

- Massive Ca²⁺ influx:

- Non-selective cation channel opens

- Ca²⁺ floods into neuron

- Result: Intense depolarisation

- Neurotransmitter release:

- Substance P released from peripheral and central terminals

- CGRP co-released

- Glutamate release

- Immediate burning pain and neurogenic inflammation

- Neurogenic inflammation:

- Substance P and CGRP cause:

- Vasodilation (redness)

- Increased vascular permeability (edema)

- Mast cell degranulation (histamine release)

- “Flare response” around application site

Phase 2: Desensitisation (Minutes to Hours)

Acute desensitisation:

- TRPV1 channel inactivation:

- High Ca²⁺ levels trigger calcineurin (phosphatase)

- Dephosphorylates TRPV1

- Channel becomes refractory (won’t open even with stimulus)

- Calcium-dependent inactivation:

- Prolonged Ca²⁺ elevation

- Alters channel conformation

- Reduces sensitivity

Result: Neuron becomes temporarily unresponsive to stimuli

Phase 3: Defunctionalisation (Days to Weeks with Repeated Use)

Long-term effects of repeated capsaicin exposure:

1. Substance P depletion:

Classic theory (still debated):

- Capsaicin disrupts retrograde transport of NGF (nerve growth factor)

- NGF normally signals cell body to synthesise Substance P

- Without NGF signal, Substance P synthesis decreases

- Existing Substance P released and not replenished

- Result: Depleted Substance P stores in nerve terminals

Modern understanding:

- Substance P depletion is correlate, not sole mechanism

- Multiple factors contribute to pain relief

2. Nerve terminal retraction:

Histological studies show:

- Reversible loss of epidermal nerve fibers (ENFs)

- C-fiber terminals retract from superficial layers

- Density reduced by 50-80% after capsaicin application

- Regeneration: Fibers grow back over 6-12 weeks

Why this matters:

- Fewer nerve terminals = less pain signal transmission

- Temporary “functional denervation”

- Explains prolonged pain relief (weeks to months)

3. TRPV1 downregulation:

- Reduced TRPV1 receptor expression

- Decreased channel density on neuronal membrane

- Less responsiveness to noxious stimuli

4. Altered ion channel expression:

- Changes in sodium channel expression (Nav1.7, Nav1.8)

- Reduced neuronal excitability

- Less likely to generate action potentials

Clinical Applications

Topical capsaicin formulations:

Low-concentration (0.025-0.075%):

- OTC creams, lotions

- Daily application

- Cumulative effect over weeks

- Uses: Arthritis, minor muscle pain

High-concentration (8% patch—Qutenza®):

- Prescription

- Single 30-60 minute application (anesthetic required)

- Mechanism: Intense TRPV1 activation → rapid nerve terminal retraction

- Duration: Up to 12 weeks pain relief

- Uses: Postherpetic neuralgia, HIV neuropathy, diabetic neuropathy

Mechanism timeline:

Minutes: Burning sensation (TRPV1 activation)

Hours: Desensitisation begins

Days: Substance P depletion noticeable

Weeks: Nerve terminal retraction maximal, pain relief peaks

Months: Nerve regeneration, pain may return

Safety and Adverse Effects

Local effects:

- Initial burning: Expected, usually subsides with repeated use

- Erythema: Redness from neurogenic inflammation

- Rare: Severe irritation, blistering (improper use)

Precautions:

- Never on broken skin: Can cause severe irritation

- Avoid mucous membranes: Eyes, nose, mouth, genitals

- Wash hands thoroughly: Prevent accidental transfer

- Patch test recommended: Especially for sensitive individuals

Contraindications:

- Acute injuries: Not for fresh wounds

- Hypersensitivity: Severe reactions possible in very sensitive individuals

No systemic toxicity:

- Minimal absorption through intact skin

- No significant drug interactions

- Safe for long-term use (topically)

Topical vs Systemic Approaches

Comparative Pharmacology

Topical Anti-Inflammatories:

Advantages:

- High local concentration at site of pain

- Minimal systemic absorption (reduced side effects)

- Direct effect on peripheral inflammatory mediators

- No GI irritation

Mechanisms:

- Arnica: Local anti-inflammatory, reduces edema

- Capsaicin: Local neuropeptide depletion, nerve terminal effects

- Menthol: Cooling sensation, counterirritant, mild anesthetic

Limitations:

- Only affect superficial tissues (skin, subcutaneous, superficial muscle)

- Cannot reach deep joints (hip, spine)

- Not systemic anti-inflammatory

Systemic Anti-Inflammatories:

Advantages:

- Affect inflammation throughout body

- Reach deep tissues (joints, internal organs)

- Systemic pain relief

- Can address root causes (if inflammatory process is systemic)

Mechanisms:

- Ginger: COX/LOX inhibition systemically, affects all tissues

- Turmeric: Multi-pathway inhibition, widespread effect

- Willow: Systemic salicylate distribution

Limitations:

- Slower onset (requires absorption, distribution)

- Potential systemic side effects (GI, interactions)

- Lower concentration at specific site (diluted throughout body)

Combined Approaches

Synergistic strategies:

Internal + External:

- Example: Daily turmeric (systemic anti-inflammatory) + arnica gel (topical acute relief)

- Addresses both ongoing inflammation and immediate pain

Multiple targets:

- Example: Ginger tea (COX/LOX) + willow bark (additional COX) + topical capsaicin (neuropeptide)

- Hits pain from multiple angles

Acute vs Chronic:

- Acute injury: Topicals first (rapid relief), add systemics if needed

- Chronic pain: Systemics as base (reduce ongoing inflammation), topicals for flare-ups

Clinical Applications and Formulation

Evidence-Based Herbal Selection

For muscle pain (DOMS, overuse):

First-line:

- Ginger: 2-4g dried daily (internal)

- Arnica: Topical gel 2-4x daily

Mechanism match:

- Muscle inflammation → COX/LOX inhibition (ginger)

- Local swelling/pain → topical anti-inflammatory (arnica)

For joint pain (osteoarthritis, stiffness):

First-line:

- Turmeric: 1-3g curcumin daily with piperine

- Willow bark: 120-240mg salicin daily

Mechanism match:

- Chronic inflammation → NF-κB inhibition (turmeric)

- Prostaglandin-mediated pain → COX inhibition (willow)

For chronic pain with nerve component:

First-line:

- Capsaicin: 0.025-0.075% cream, 3-4x daily

- Ginger or turmeric: Systemic anti-inflammatory support

Mechanism match:

- Neuropathic pain → Substance P depletion (capsaicin)

- Background inflammation → Systemic anti-inflammatory

Formulation Principles

Synergy considerations:

1. Pharmacokinetic synergy:

- Piperine + curcumin: Enhances absorption

- Fat + turmeric: Improves bioavailability

2. Pharmacodynamic synergy:

- Ginger + willow: Dual COX inhibition from different sources

- Turmeric + ginger: NF-κB inhibition + dual COX-LOX

3. Route synergy:

- Internal ginger + topical arnica: Systemic and local approaches

Extract standardisation:

Why it matters:

- Herbal potency varies (growing conditions, harvest time, storage)

- Standardisation ensures consistent dosing

- Research uses standardised extracts

Examples:

- Willow bark: Standardised to % salicin (120mg, 240mg)

- Turmeric: Standardised to % curcuminoids (95% curcuminoids = pharmaceutical grade)

- Ginger: Sometimes standardised to % gingerols (5-10%)

Dosing Strategies

Therapeutic windows:

Ginger:

- Preventive/mild pain: 1-2g dried daily

- Moderate pain: 2-4g dried daily

- Divided doses: 3x daily (matches pharmacokinetics)

Turmeric:

- Maintenance: 1g curcumin daily

- Therapeutic: 2-3g curcumin daily

- With meals: Improves absorption, reduces GI upset

- Always with piperine: 20mg or 1/4 teaspoon black pepper

Willow bark:

- Mild pain: 120mg salicin daily

- Moderate pain: 240mg salicin daily

- With food: Reduces stomach irritation

Capsaicin:

- Low-dose: 0.025% cream, 4x daily

- Moderate: 0.075% cream, 3-4x daily

- Consistency: Daily use for 2-4 weeks to see full effect

References

Black, C. D., Herring, M. P., Hurley, D. J., & O’Connor, P. J. (2010). Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces muscle pain caused by eccentric exercise. Journal of Pain, 11(9), 894-903.

Chandran, B., & Goel, A. (2012). A randomized, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of curcumin in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Phytotherapy Research, 26(11), 1719-1725.

Chrubasik, S., Eisenberg, E., Balan, E., Weinberger, T., Luzzati, R., & Conradt, C. (2000). Treatment of low back pain exacerbations with willow bark extract: A randomized double-blind study. American Journal of Medicine, 109(1), 9-14.

Kuptniratsaikul, V., Dajpratham, P., Taechaarpornkul, W., et al. (2014). Efficacy and safety of Curcuma domestica extracts compared with ibuprofen in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A multicenter study. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 451-458.

Yaksh, T. L., Farb, D. H., Leeman, S. E., & Jessell, T. M. (1979). Intrathecal capsaicin depletes substance P in the rat spinal cord and produces prolonged thermal analgesia. Science, 206(4417), 481-483.

Srivastava, K. C., & Mustafa, T. (1992). Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in rheumatism and musculoskeletal disorders. Medical Hypothesis, 39(4), 342-348.

Manayi, A., Vazirian, M., & Saeidnia, S. (2015). Echinacea purpurea: Pharmacology, phytochemistry and analysis methods. Pharmacognosy Reviews, 9(17), 63-72.

Bone, K., & Mills, S. (2013). Principles and practice of phytotherapy: Modern herbal medicine (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone.

Disclaimer: This guide is for educational purposes only and is not medical advice. Consult qualified healthcare practitioners before using herbal remedies, especially if pregnant, nursing, taking medications, or having medical conditions.

Note on Pricing: All prices mentioned in this guide are approximate and based on New Zealand suppliers as of December 2025. Prices vary by supplier, season, and market conditions. We recommend checking current prices with your local suppliers.